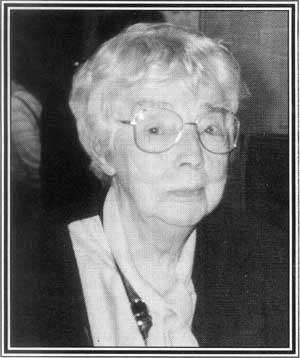

Stella Patri died March 31, aged 104, at

the home of her son Remo in Sonoma, California. She was a renowned

bookbinder and paper conservator, and adoyenne of the Bay Area

bookbinding community for over forty years.

Stella Patri died March 31, aged 104, at

the home of her son Remo in Sonoma, California. She was a renowned

bookbinder and paper conservator, and adoyenne of the Bay Area

bookbinding community for over forty years.

Although she began her bookbinding career when most people are thinking about retirement, her enthusiasm and determination enabled her to pursue her studies in the field in Italy, France, England and Japan, and to continue her work in the restoration business in San Francisco, inspiring many younger bookbinders and making many friends. Her contribution to the recovery of priceless books after the Florence flood of 1966 has been well recorded: she made three visits to Italy to help with the efforts.

Stella was a founding member of The Hand Bookbinders of California, a member of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, the Institute of Paper Conservation, Designer Bookbinders, and a long-time member of the Guild of Book Workers. She was made an Honorary Member of the Guild in 1993 and was given the Oscar Lewis Award by The Book Club of California in 1995. Many bookbinders and conservators, both in the Bay Area and across the country, were influenced by her and continue to practice the craft with the characteristic passion she brought to it.

Stella Nicole was born on November 1, 1896, in Montreal, Canada, and moved with her family to San Francisco in 1900. After the devastating earthquake of 1906, the family returned to Montreal until they were able to move back to California. Stella's father died in 1917, and her mother supported the family as a "Parisian Dressmaker." Stella became an expert milliner at the age of 18, working as a production artist at Gumps

in San Francisco. She married Giacomo Patri, an Italian-born artist, in 1925. Throughout the twenties and thirties they became involved in social activism, and during the Second World War Stella, a lifelong pacifist, became a journeyman welder on the Liberty Ships, and later worked with the Red Cross.

She first learned bookbinding with the noted teacher Octavia Holden in 1938, and recalled being impressed with an exhibition of bookbinding at the 1939 World's Fair, put on by Eleanor Hesthal and Peter Fahey. It wasn't until 1958, however, once her three children had grown up and she was divorced, that she returned to the craft, studying part-time with Herbert and Peter Fahey, while working in various local book shops. The Faheys had studied in Germany with Ignatz Wiemeler, and were the center of the bookbinding teaching community in San Francisco for many years, teaching, among others, Eleanor Hesthal, Jane Grabhorn, Lewis and Dorothy Allen, Leah Wollenberg, Barbara Hiller, Eleanore Ramsey, Duncan Olmsted, Sheila Casey and Gale Herrick.

At the age of 62 Stella decided to study book restoration. After two years of correspondence, she was accepted at the Istituto Centrale per la Patologia del Libro in Rome, where she studied paper repair for four months under Dr. Franka Manganelli. There followed a stint in Paris, studying with the finisher Jules-Henri Fach. She then moved to London, and studied leather repair with Mr. Sidders, who had worked at Rivière and Son. While in England she made contact with all the famous bookbinders she could, including Roger Powell, Peter Waters, Anthony Gardner and Sidney Cockerell. Of Roger Powell she said, "He and his wife Rita put me up for the night, because they lived out of town, and there was no transportation back to London that evening. The English are just wonderful. They'd never seen me before, and here's this stupid woman who doesn't even know what kind of questions to ask, and wants to know all about bookbinding: evidently an amateur, you know. He was the finest bookbinder in England, Roger Powell."

Once back in San Francisco, Stella began her career as a book restorer, working for many years for the University of California Medical Center. In 1966, while in London with her youngest son, she read about the Florence Flood in the newspaper. "Oh, I have to go there," she said, and wrote to the cultural attaché in Rome ("It's no use writing to the Italians, they're too excitable, they're in this mess"), and after a month, hearing nothing, she got on the train to Rome, to find Roger Powell waiting for her. Thus began a month of volunteer work on the water-damaged, mud-soaked books, alongside Bernard Middleton, Peter Waters, Anthony Cains and Chris Clarkson. She returned twice more to Florence, contributing to the restoration effort and making many lifelong friends around the world.

In June last year she had a special visit. Her friends Margaret Johnson, Michael Burke and Dominic Riley popped in for tea, bringing with them her old friend Bernard Middleton and Flora Ginn. Frustrated by old age and poor eyesight, she nevertheless brightened up as she recalled the names of mutual friends and colleagues she had met with Bernard in Florence, and the memories came flooding back, so to speak. Bernard was obviously delighted to be able to see her again, and to introduce her to Flora, his successor. And so, the craft survives.

Infected with an enthusiasm for learning, Stella spent much of her time traveling the world, pursuing her research into restoration. She visited China, Japan, Korea, Turkey, and the Balkans. She continued to work in bookbinding well into her nineties, when she also visited Montreal to research her family tree. At 95, she returned to Japan to see the cherry blossoms one last time. On the eve of her 95th birthday she appeared in Herb Caen's column in the San Francisco Chronicle, saying, "I plan to be around another nine years and two months, so I can say I lived in three centuries," and confessed that her secret was "I take no medicine except white wine."

Stella Patri's 100th birthday was a special occasion not only for the Hand Bookbinders of California, the group she helped found and whose events she never missed, but also for the City of San Francisco. At her birthday celebrations Mayor Willie Brown declared November 1st 1996 "Stella Nicole Patri day." In her late nineties, she had started passing on her equipment and tools, giving many of them away to younger binders who she knew would make good use of them (her Japanese brushes she could not part with). This was a wise move: not only did she make sure that the contents of her bindery went to good homes while she was still around to organize it, but she also ensured that for many years to come, new generations of bookbinders would think of her whenever they picked up that special tool or spool of silk, bestowed on them by a beloved colleague, mentor, and true friend.