"If These Walls could Talk ...": Treatment of the Crawford Dining Room Collage

by Judith EmprechtingerPresented at the Book & Paper Group Session, AIC 28th Annual Meeting, June 8-13, 2000, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Received for publication Fall 2000.

Abstract

In preparation for the exhibit Folk Art of Social Change, the Philadelphia Folklore Project discovered the Crawfords' dining room. The Crawfords' dining room was not an ordinary dining room but an important meeting place and office for people involved with the Civil Rights Movement in Philadelphia. Over the years the Crawfords, well-known political activists since the late forties, had turned their dining room into a large scrapbook exhibiting a unique collection of political memorabilia. More than four hundred items, including posters, buttons, newspaper cutouts, brochures, front pages of magazines, photographs, postcards, etc., cover more than 230 square feet of the dining room. The Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts was employed for the challenging work of removing the entire wall-covering collage and remounting it as one of the centerpieces of the exhibit. This paper describes the various treatment steps, the difficulties that were encountered due to the type of materials involved, and the fact that the removal took place while the dining room was still in use by the Crawfords, how the problems were solved, and the compromises that needed to be made due to limited funding and time frame for the treatment.

Introduction

On the occasion of the twenty-eighth annual meeting of the American Institute for Conservation taking place in Philadelphia, this conservation treatment project was presented because it relates to Philadelphia's history. This project, the removal and remounting of a contemporary collage, is of a very unusual character. When thinking about Philadelphia's history, we always refer to the Declaration of Independence. While not being the Declaration of Independence, this collage certainly is a declaration of independence.

The Crawford Dining Room Collage

The Philadelphia Folklore Project, a public agency that documents, supports, and presents local folk art and culture, was planning a new exhibit called Folk Arts of Social Change, focusing on Philadelphia activism from 1930 to the present.

During field work for the exhibit, the names of Bill and Miriam Crawford came up due to Bill's involvement with the Communist Party and his bookstore, the New World Book Fair in West Philadelphia. Open from 1961 to 1974, the store was ground-breaking in featuring Marxist, African American, and gay literature. It was also an invaluable resource and gathering place for people with progressive causes. Many Philadelphia activists remember this place and how important it was for their education, not only because of the books, but also because of the Crawfords and the people they met in the store.

In preparation for the exhibit the curator of the Folklore Project interviewed the Crawfords and learned about Bill's upbringing as the great-grandson of a runaway slave. The anti-slavery movement was therefore part of everyday discussions. Later on Bill Crawford became involved in Marxism and the struggle of the African American community for freedom. "Freedom was my badge, which I got from my grandfather and my great-grandfather, having been a slave and escaped, that was a very powerful influence—the need to understand what it meant for a slave to break out, and not just a man but for a woman with a baby in her arms." 1

Fig. 1. The Crawfords

Fig. 2. The Crawford's dining room collage, before treatment

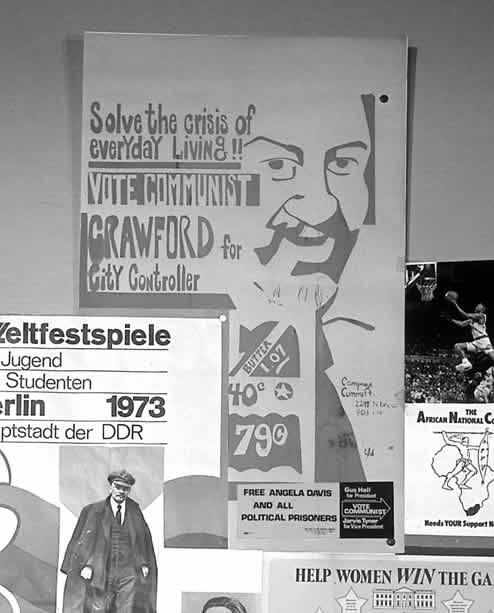

Fig. 3. Bill Crawford's campaign poster

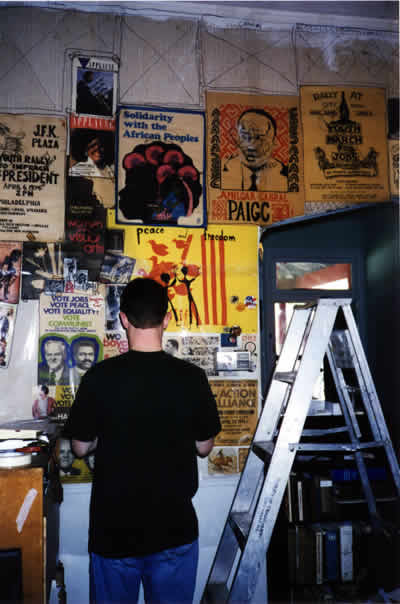

When the curator of the Folklore Project stepped into the Crawfords' dining room to begin the interviews, she was astounded by this unusual collage, which covered the entire dining room walls (figs. 1-2). This dining room was not an ordinary room but had been used as an important meeting place and office for people involved with the Civil Rights Movement in Philadelphia. Over the years the couple had turned the room into a large scrapbook exhibiting a unique collection of political memorabilia. More than four hundred items, including posters, buttons, newspaper cutouts, brochures, front pages of magazines, photographs, postcards, etc., cover more than 230 square feet of the walls. The collage chronicles the Crawfords' political development, their beliefs, and four decades of political and social life in Philadelphia. Besides demonstrating the couple's involvement in the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Anti-War movements, Bill's own campaign as city controller is recorded within this unusual collage (fig. 3). There are posters representing political issues, but also literary and musical favorites, cartoons and photographs relating to the Crawfords involved lives during the last decades. Each piece has its own story to tell, and as a whole these "walls of memory" are unusual witnesses of Philadelphia's political and social history of the last decades. The Crawfords don't regard themselves as artists. The collage is merely part of their lives.

When the Folklore Project learned of the Crawfords' plans to move and sell their house, the idea was proposed to save the collage as a centerpiece for the upcoming exhibit. Bill and Miriam Crawford donated their collage for this purpose and the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts was employed to perform the removal and remounting .

Examination and Treatment Planning

The goal of the conservation treatment was to safely remove the collage elements and remount them in their original configuration without changing the general appearance of the collage.

During an initial examination senior paper conservator Anne Downey found that the collage elements were adhered directly to wallpaper and overlapping each other with a polyvinyl acetate emulsion (PVA). The PVA was not applied over the whole surface, but in swirls and rectangles and whatever suited the artist's fancy. A smaller number of items were attached using pressure-sensitive tapes, pushpins, and nails. There were small void areas throughout and on top of the collage exposing the underlying wallpaper.

Since the wallpaper was adhered to the walls using a water-based adhesive, the idea was to remove the collage by removing the wallpaper. The thought was to spray the collage until the water soaked through to the wallpaper, softened the adhesive, and released the wallpaper. As a unit the collage and wallpaper could be peeled off the wall by rolling over a supportive sheet of Mylar and again as a unit could be mounted onto alkaline mat board. These mat board panels could then be attached with continuous Velcro strips onto the reconstructed walls of the Crawfords' dining room in exhibit.

The client was informed that washing and deacidifying the poor quality collage materials would be desirable. However, due to a short time frame and a tight financial situation, extensive stabilization of the collage was not possible. The client was advised to monitor the collage over time and to limit light exposure.

Treatment

The treatment was structured into three steps:

- Documentation

- Removal

- Remounting

1. Documentation

Fig. 4. Documentation

First an accurate documentation of the collage was executed by a volunteer (fig. 4). The exact placement of all collage items was recorded by tracing the outlines of the items with marker onto sheets of Mylar. This included placement of nails, thumbtacks, buttons, and pressure-sensitive tapes. Great care was taken in areas where several layers were adhered over each other, since some of the items were only partially visible.

2. Collage Removal

Armed with all the tools and devices we thought we could possibly use, we arrived on site for the scheduled removal of the collage. Since the Crawfords were still living in the house at the time of the removal, we tried to be as least invasive to their living spaces as possible. Fitting two ladders between the furniture and working on items above and close to doors was quite a challenge. Additionally, Philadelphia was experiencing a heat wave, making us work under tropical conditions.

We started the removal of collage elements that could be taken down mechanically by removing pushpins and cutting pressure-sensitive tapes along the edges of the items. Items made of heavyweight paper, photographs, and postcards could be lifted by sliding a Teflon spatula between the wallpaper and the adhesive film. In these instances the paper support was strong enough, and the items would simply split away from the wall by skinning the wallpaper. The items were then catalogued for remounting.

The majority of the collage needed to be removed by wet treatment. We decided to proceed with the removal in two- to three-foot-wide sections and scored along their outline with a scalpel. Due to the nature of the collage some collage elements needed to be cut; however these cuts could be made unobtrusively without interfering with the composition of the image.

Fig. 5. Collage removal

Fig. 6. Collage removal

Media and paper supports were tested for stability to water and the first section was sprayed and covered with Mylar. Special care needed to be taken to avoid the formation of tidelines between sections. After an hour of repeated applications of water, I tried to lift the collage in one corner and found that the moisture had not penetrated to the wallpaper. After another half-hour the result was still the same. It appeared that the PVA film acted as a barrier making the penetration of the water to the wallpaper impossible. Additionally, many collage elements did not lie flat against the wall. Without direct contact the water could not transfer to the wallpaper. In order to remove the wallpaper and collage together it was necessary to lift the top edge of the section and spray the interface between wall and wallpaper until the adhesive released (figs. 5-6). In this way we worked our way down, spraying, waiting, peeling, and rolling, inch by inch, repeating this process for the 30,240 square inches of the dining room. We tried various methods to accelerate the process by using steam, hot water, and water-alcohol. With the same results. The water-alcohol solution seemed to accelerate the process somewhat; however with the Crawfords living in the house, we decided to use it only as an "emergency tool."

While removing a section I noticed a tearing of the wallpaper support and upon unrolling realized that some areas of the collage had creased. I soon realized that we had to deal with more than one problem:

- First, rolling the many paper layers over Mylar caused tension, creasing the inner layer—the collage—and tearing the outer layer—the wallpaper.

- Another problem was that the collage items expanded in different ratios when wetted out. Many of the modern papers grew substantially in size. The expansion movement of the paper was restricted by the adhesion to the wallpaper, causing odd undulations and creasing. The problem was particularly severe in areas of many overlapping items. Laying Mylar atop these smooth undulations caused creasing.

It appeared that through wet treatment we were able to remove the collage, but at the same time it caused a number of problems. Time was running out and the collage needed to be removed. I decided that a certain level of imperfection was acceptable in favor of saving the collage that otherwise would be destroyed. To prevent any problems, several new treatment steps were used:

Fig. 7. Collage removal using cardstock support

Fig. 8. Gradual removal in small sections

- First, to reduce problems during removal, we reduced the size of

the sections and used a large cardstock roll as a new support in

addition to the Mylar (fig. 7). Rolling the

sections over a large curved surface kept the creasing to a minimum.

I had originally felt that keeping together as many overlapping

items as possible and making few cuts would preserve the originality

of the collage. However, this was not possible. In some instances

the tension could be released by making small unobtrusive cuts along

the edges of items. In other cases overlapping items needed to be

completely separated (fig. 8).

Fig. 9. Washing

- Second, after the removal, taking off the wallpaper and allowing the collage elements to freely expand could eliminate some problems. In our initial proposal we were planning on leaving the wallpaper and collage together, because we expected difficulties in removing the PVA film from the verso of the collage. However, we found that the poor quality, short-fibered wallpaper became soft and pulpy when wet and could easily be peeled off, simply leaving the PVA layer on the verso of the collage. We found it was easiest after removal to transport the sections to the lab and immerse them in water (fig. 9). After soaking for some time the wallpaper could be lifted from the collage, and any of the heavy discoloration given off by the wallpaper was rinsed off. Considering the poor condition of the wallpaper this additional step became also necessary, since it was not advisable to remount the collage in contact with such deteriorated material.

Another potential problem was the flattening of the collage after the bath. A certain amount of pressure was necessary to work out creases; however there was the risk of pressing the thick layer of PVA into the paper, creating a relief pattern and altering the surface of the collage. The best results were achieved by allowing the collage items to air dry and while still damp placing them between felts.

Some thoughts were spent on the possibility of removing the collage without the wallpaper. Several attempts were made using a variety of systems, but failed. The location of the PVA film was too unpredictable and the wallpaper needed to be wet to the point where it was falling apart in order to release the PVA film.

The whole removal took 180 working hours.

3. Collage Remounting

Since we altered the initial proposal by removing the wallpaper layer and reducing the size of the sections, the remounting of the collage also needed to be rethought.

I reevaluated the material to be used as a mounting base. Mat board seemed somewhat heavy and tended to warp when handled. My attention was drawn to alkaline corrugated board.2 In sheets of four by six feet, this lightweight yet stiff material fulfilled all of the characteristics I was looking for. Besides its archival qualities, corrugated board is stable enough to withstand travel and handling and is easy to cut. My only concern was that the thickness of the board combined with the Velcro would make the panels stand almost one half inch off the wall. This effect might look quite awkward. This was not a concern for the exhibit designer, other than that the reconstructed dining room needed to be slightly larger to accommodate the additional space.

We further discussed the best way to recreate the image of the Crawfords' dining room in exhibit. We agreed to paint the walls of the exhibit dining room in a grayish tone imitating the color of the wallpaper. Small void areas within the collage were filled with pieces of the original wallpaper. When the panels were attached to the reconstructed walls the gray background gave the impression of continuous wallpaper in uncovered areas.

Fig. 10. Laying out collage elements

Fig. 11. Tracing outline of a section

Fig. 12. Cutting jig-sawed edges

Fig. 13. After treatment: two completed panels

The remounting process involved several steps, starting with laying out all the items according to the traced Mylar (fig. 10), determining the size of each panel (fig. 11), cutting the board (fig. 12), and finally attaching the wallpaper pieces and the collage elements (fig. 13) The cut edges were wrapped in Japanese paper as a protection and to hide the corrugation in areas where it would otherwise be visible. Special attention was paid to "jigsawed" edges that needed to fit into the adjoining panel. When attaching the collage elements, I decided to apply paste only onto the PVA layer as opposed to pasting out the whole verso. This would prevent the thick layer of PVA from being pressed into relief. This technique restored the original appearance of the collage because the items were attached in the same points as before and thus did not look too flat. Collage elements that were originally attached by pushpins and nails were attached in the same manner and additionally were pasted at all corners to ensure a secure attachment. We had a lot of discussions as to whether to remove the many pressure-sensitive tapes and substitute them with conservation tapes or whether this would interfere with the authenticity of the artist's materials. Since time and financial factors were predominant, the decision was already made. New pressure-sensitive tapes were simply applied over the old sliced tapes.

The remounting took 150 hours, including 50 hours of volunteer work by employees, friends, and family of the Conservation Center to help with the project.

Fig. 14. The Crawfords' dining room in exhibit, after treatment

Fig. 15. The dining room: before treatment

Fig. 16. The dining room: after treatment

After 320 total hours spent working in the Crawfords' house and in the lab we were looking forward to the exhibit opening. The Crawfords' dining room looked great. Standing in the reconstructed room felt like being in the Crawfords' house again, only this time with air conditioning! The exhibit got excellent reviews from major newspapers, mentioning the Crawfords' dining room in word and image. We all felt enthusiastic about having saved this piece for the Philadelphia community (figs. 14-16).

After the exhibit the feedback from the Folklore Project about handling the panels was very positive. The Folklore Project also applied for funding to store the panels in flat storage files and just recently received a grant for this housing project. Each panel will be housed in an archival, acid-free cardstock folder with an additional corrugated board as a support material for safe handling. A maximum of two panels will be stored per drawer. The folders will also protect the collage from abrasion. In the future the Folklore Project is planning to mount the panels on permanent exhibit once adequate space has been found.

The Crawfords' collage is a type of its own, a tangible illustration of the couple's beliefs and an outcry and appeal for change. The collage lived through the people. I hope that in the future the collage will be exhibited again in order to fulfill its purpose of reaching the people with its message.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank technician Sue Bing and intern Rachel Wales for the great work they did, Anne Downey for encouraging me to give this talk, and Chad Johnson for his patience with computer questions. I also thank the many people that helped and volunteered during this project: Ingrid Bogel, Donna Farrell, Dawn Heller, Martha Heuser, Amanda Hunter, Glen and Thad Ruzicka, Mary Schobert, Rolf Kat, Bill and Miriam Crawford; and Kari Ytterhus, Deborah Kodish, and Teresa Jaynes from the Philadelphia Folklore Project for providing me with background information.

Illustration credits: W. Brown, Susan Bing, Matt Thomson, Judith Emprechtinger.

Notes

1. Text from the exhibit Folk Art of Social Change, 1999; interview with William H. Crawford conducted by the Philadelphia Folklore Project.

2. Artcare corrugated board with Zeolite Molecular Traps, Nielsen & Bainbridge, NJ.

Judith EmprechtingerBook and Paper Conservator

Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts

Publication History

Received: Fall 2000

Paper delivered at the Book and Paper specialty group session, AIC 28th Annual Meeting, 8-13, 2000, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Papers for the specialty group session are selected by committee, based on abstracts and there has been no further peer review. Papers are received by the compiler in the Fall following the meeting and the author is welcome to make revisions, minor or major.