|

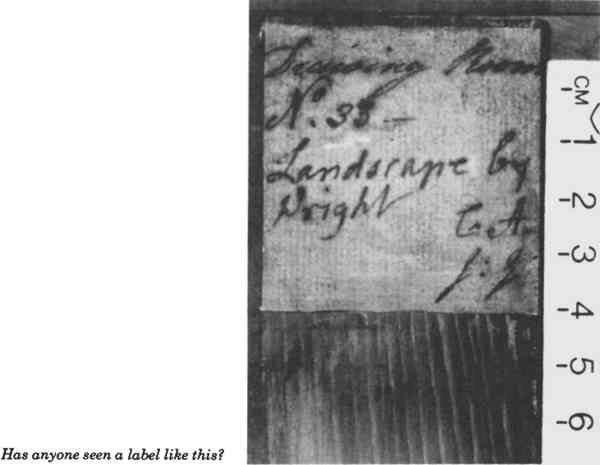

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR1.1 TO THE EDITOR:IN THE Master of Art Conservation Program at Queen's University we are undertaking research on some aspects of late 18th–century English painting techniques. Our research would be greatly facilitated if we could establish the whereabouts of paintings bearing inventory labels like the one illustrated. If readers have come across such a label, would they be so kind as to contact us and give the source reference?

1.1 TO THE EDITOR:IN THE fall of 1989 I was consulted about a damaged ethnographic whalebone carving and decided to try to obtain a sample specimen of whalebone for comparative examination of the microscopic features, fracture characteristics, etc. However, when I called a store that sells natural history materials I learned that it is illegal to buy or sell any part of a whale because this animal has been designated an endangered species. An “Endangered Species” is any animal or plant listed by regulation as being in danger of extinction and protected by law. There is also a listing of “Threatened Species,” any animal or plant which is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future. Laws protecting Threatened Species are somewhat less restrictive. Historic and artistic objects have sometimes been made whooly or in part of materials derived from species now considered endangered and protected by law. In order to find out how I could legally The laws on this subjkect are many and complex. They include:

It is not possible to synopsize all the laws, and in each case one should check to see which laws apply and contact the Regional Office if in doubt. (The central office of each numbered Region is: Region 1(includes Hawaii)—Portland, Oregon; Region 2—Albuquerque, New Maxico; Region 3—Twin Cities, Minnesota; Region 4 (includes Puerto Rico)—Atlanta, Georgia; Region 5—Newton Corner, Massachusetts; Region 6—Denver, Colorado; Region'7—Anchorage, Alaska. A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service publication that lists all the endangered and threatened wildlife and plants worldwide, as of January 1, 1989, runs to 34 pages (10 of which apply to plants). Each species must be dealt with separately to determine the legalities of its commerce. For example, there is an import ban on African elephant ivory but not yet on its interstate commerce; African ivory is plentiful in the U.S. and can be obtained redily if one knows where to look for it. However, the ivory of Asian elephants is naturally less available (only males grow tusks, which are generally smaller than those of African elephants), and both importation and interstate commerce of Asian ivory is prohibited. Due to international concern about the decimation of African elephant populations caused by poaching for ivory, this species has just been upgraded from CITES Appendix II and now, like the Asian elephant, is listed in Appendix I, prohbibting all commercial trade in ivory (and other materials) from both species among the 103 CITES party nations. However, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has recently decided to allow commerce of antiques which can be documented to be at least 100 years old, as they clearly do not represent recently killed animals. As an example of the complexity of the laws, a pre-Act (i.e. pre-1973) specimen of Asian elephant ivory younger than 100 years old can be legally possessed, but if offered for sale it loses its pre-Act status and a permit is needed; whereas if it is documented as over 100 years old it is completely exempt. But it will require CITES permits for importation and exporation whatever its age. Regulations regarding legal receipt, transportation and possession of donated ivory are similarly complicated. A few exceptions are allowed within wildlife protection laws, notably for the taking of endangered species by native peoples who have traditionally done so (e.g. Eskimos), and for “scientific research.” IT was explained to me, however that the latter refers only to research that will benefit the survival of the species and gtherefore no permit would be granted for art conservation research. To legally acquire and possess a specimen of, for example, walrus tusk, there are three possibilities:

The consequences of illegal purchase, importation or exportation, and possession can be serious. Thousands of dollars in fines and possible imprisonment can be imposed. At present conservators wishing to examine parts and products from endangered species in order to familiarize themselves with their appearance have a few legal ways to do this:

In July of 1989 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service opened the first National Wildlife Forensics Laboratory, located in Ashland, Oregon. According to an undated, unnumbered brochure published by the Service, “The primary mission of the laboratory is to make species-specific identifications of wildlife parts and products seized as evidence, and—much like a police crime lab—to match suspect, victim and crime scene together through the examination of physical evidence.” The first part of this mission is of interest to art conservators because we often must attempt to do the same thing for components of historic and artistic works, in order to help determine their origin and authenticity and for optimum interpretation of their present condition and of any alterations, natural or imposed. When completely staffed, the new laboratory will have approximately eighteen forensic scientists, seven lab technicians, and five clerical support personnel. The three analytical sections are designated Morphology, Serology and Criminalistics. I spoke recently with the Director, Kenneth Goddard, and he expressed a willingness to help art conservators even though our goals are not part of their mission. As Mr. Goddard explained, every time members of his stall go to court they are giving away technical information to the lawbreakers, so they can certainly also share their expertise with us! Conservators, scientists, and curators who think there should be an additional exemption for the purposes of education and research pertaining to art conservation may wish to petition the Director of the U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife. Perhaps there could be a research permit that would allow legal acquisition and possession by art conservators of samples from seized materials. I am willing to work with other members of AIC to present this issue to the AIC Board. Jean D.PortellSculpture Conservation, 13 Garden Place, Brooklyn, NY 11201 |