CONSERVATION TREATMENT OF TIBETAN THANGKAS

ANN SHAFTEL

2 PROBLEMS IN THE CONSERVATION OF THANGKAS

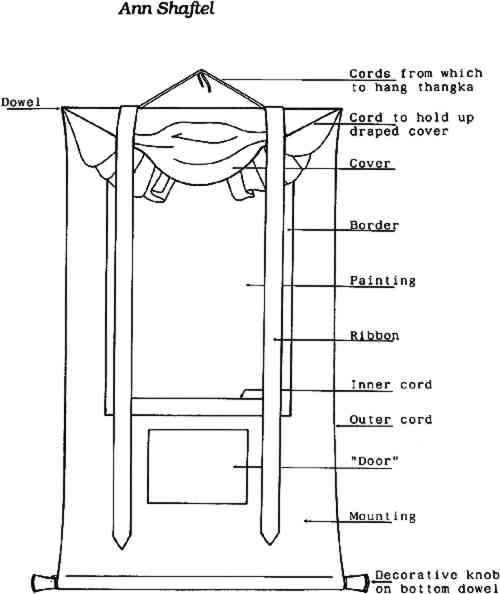

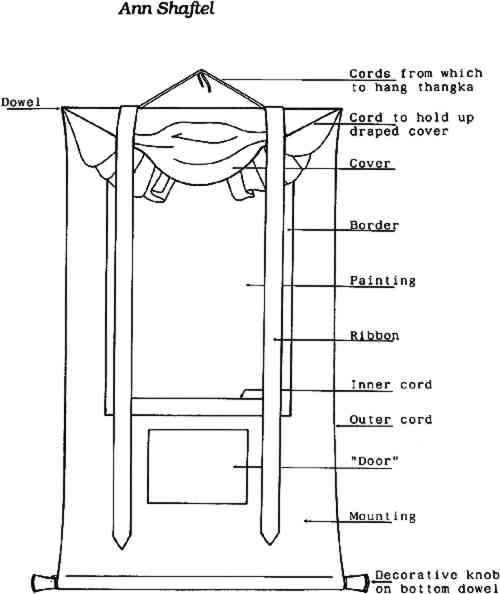

TIBETAN THANGKAS are complex objects. A popular form of thangka might consist of a central painting (cotton support) mounted in textile borders (silk with cotton lining) that have wooden dowels on the top and bottom and sometimes protective leather corners on top edges of the mounting and decorative metal knobs on the bottom dowel (fig. 1; for a more complete description, see Shaftel 1986). A thangka is a prime example of “inherent vice.” Each material reacts differently to handling, aging, changes in temperature and humidity, and so forth.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of sample Tibetan thangka.

|

Thangkas also have a complex religious significance and function (Trungpa 1975). The iconographic content of the picture panel is a guide to meditation. Traditionally, the teachings are passed on from teacher to student meditator. If a conservator treating a thangka is without extensive training in both iconography and painting technique, an attempt to inpaint is fraught with opportunities for error.

The mounting is an inherent part of the thangka (Schoenholzer-Nichols 1988). Even when its painting has been removed and is displayed separately, it remains a painting that belongs in a thangka.

In 21 years of research, I have encountered many well-intentioned mistakes in the conservation treatment of Tibetan thangkas. These include treatments that have:

- removed and discarded the mounting altogether and treated the painting with methods appropriate for a Western oil painting; including matting and framing the painting in a Western aesthetic

- removed and discarded the mounting and treated the painting with methods appropriate for a Chinese or Japanese scroll painting on silk or paper, then mounted the painting in a scroll-painting aesthetic

- left the painting in the mounting and lined it in situ with a method appropriate for a Western-style painting

- inpainted without an understanding of the iconography or original painting methods

- left the painting in place in the mounting and trimmed the top and bottom dowels off, then framed the entire thangka in a traditional Western-style frame

- removed and discarded the cover

- given every mounting a strong chemical treatment for bacterial growth, when perhaps mild cleaning, airing, and proper display and storage would have sufficed

- lined the paintings with an aqueous adhesive mixture of animal glue and wheat flour, risking moisture penetrating the ground and paint layers from behind.

When the conservator is faced with a painting long since removed from its mounting, several options are available, each presenting a possibility for error. Notable errors have been:

- a new mounting, copied from another thangka, in which style, color, and proportions do not suit the painting

- a new mounting not structurally strong enough to hold the painting in plane

- a painting sewn into a replacement mounting improperly and unevenly tensioned, causing eventual damage to the support, ground, and paint layer

- a painting rolled for storage or shipping after being secured in a new mounting so that the support was creased, causing cracks and losses in the ground and paint layers.

|