THE OPENING OF CONSECRATED TIBETAN BRONZES WITH INTERIOR CONTENTS: SCHOLARLY, CONSERVATION, AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONSCHANDRA L. REEDY

ABSTRACT—Tibetan Buddhist and Bon-p� statues are consecrated before being used for worship. During the ceremony, objects are often sealed inside hollow-cast pieces. Many types of objects have been found when statues were opened for museum study. Although statue contents comprise an interesting range of items, they were only rarely found to contain information relevant to the date or place of manufacture of a piece. Much time and expense are generally required to fully analyze and conserve the removed contents. A survey of Tibetan religious teachers revealed strong opinions that opening a statue is a desecration that cannot really be rectified. The conclusion of this research is that the data obtained from removing and studying statue contents are not useful enough to justify further statue openings. 1 INTRODUCTIONALMOST ALL copper-based statues produced in the Himalayan regions of northwest India, Tibet, and Nepal over the past 1,500 years or more were made for religious purposes. The majority of the surviving metal statues from Tibet are Buddhist; a few statues have also survived from the Bon-p� traditions, the shamanistic indigenous religious practices of Tibet. Consecration ceremonies were and still are performed on all statues from these traditions prior to their use. About half of the extant Tibetan bronzes are solid metal, and half are a relatively thin layer of metal cast around a clay core. Frequently, some of the clay core, especially from the area in the center of the torso, is removed after casting to leave a hollow area into which sacred objects are inserted during the consecration ceremony. After a background discussion concerning the purposes and components of a consecration ceremony, this article reports the results of research regarding the opening of consecrated statues for study of their interior contents. It discusses which statues have been opened, what items have been found as interior contents, what knowledge has been obtained through studies of the contents, what effects opening the statues might have on the state of preservation of the contents, what Tibetan Buddhist practitioners think about the opening of consecrated statues in a museum context, and whether or not museum staff should continue to open Tibetan statues for interior content studies. 2 CONSECRATIONTHIS INQUIRY into the content of consecration ceremonies began with a survey of the literature, including both summaries of various older Tibetan texts and writings of modern Tibetan practitioners. A questionnaire on the viewpoints of living practitioners The consecration ceremony first purifies an image in order to make it suitable for habitation by the Buddha or other deity involved. Then it invests the statue with the power and presence of that deity. Unless it has been consecrated, a statue is not considered suitable for use in religious practices. The consecration ceremony can only be performed by a fully qualified person considered knowledgeable and proficient in all the ritual activities that need to be done; he must be stable, calm, wise, patient, honest, and without pretensions and must have received the required initiations and teachings. The deity is invited to the statue through the power of meditation, the potency of the ritual, and the devotion of the ceremony's hosts. After being invited, a deity is drawn into the statue to be consecrated, and its presence is sealed by the procedures of the ritual. The ceremony can be performed either in a monastery or in a layperson's home. It is repeated, when circumstances allow, once a year. After consecration the image must be kept clean and the spirit of consecration kept alive through the religious study and practice of those around it (Sharpa Tulku and Perrott 1985). The ritual can be used to consecrate any representation of the Buddha's body, speech, and mind. The Buddha's body is most often represented by statues or paintings, speech by scriptures, and enlightened mind by a stupa (ch�ten)1. Other more ordinary objects can also be consecrated, such as ornaments, houses, gardens, wells, or mantra beads. (A mantra is a sequence of syllables whose sounds, when recited in tantric meditations, are intended to promote a state of identification with the deity being invoked; the exact number of recitations to be performed is usually specified in the meditation text, and a string of beads is the usual device for keeping count.) There are many reasons for consecrating an object. For example, greater faith and respect for the object is generated when great lamas have performed consecration rituals for it. The ritual is also used to clear an area of obstacles and make it more peaceful and free from disease, to create conducive conditions for meditation, and to increase the lifespan, happiness, and wealth of the inhabitants of an area (Panchen �trul Rinpoche 1987). During the consecration ceremony, holy articles are sometimes sealed inside the statue. While the objects are being placed inside the piece, the deity is invoked and infused into the work of art through the use of appropriate hand gestures, mantras, and visualizations. According to Giuseppe Tucci's summary of Tibetan Buddhist texts concerning consecration (Tucci 1949, 1:309–310) and modern Tibetan scholars on the subject (Kazi 1966, 8–10;Dagyab 1977, 1:32–33), a wide variety of holy articles can be selected for insertion. These objects usually include sacred writings (mantras or excerpts from scriptures), with specific ones being considered most appropriate for placing in particular parts of the statue. The physical relics of holy persons can also be inserted. These relics may be actual parts of the body (hair, teeth, pieces of skull or bone, and ashes) or objects that came in close contact with the holy person during his or her lifetime. Other items frequently inserted are sacred images (made of metal, wood, or clay) and medicinal or purifying plants such as powdered saffron flowers or pieces of juniper tree incense. Whatever is most available and appropriate to the specific situation can be included. Tarthang Tulku, Head Lama of the Tibetan Nyingma Center in Berkeley, California, described the preparation and insertion of objects into a statue during a typical modern consecration ceremony (Tarthang Tulku 1989). In the center of the statue one might For each statue, special writings would be inserted. The selection of writings to include depends upon the meditation practices and the purposes of the statue. On an auspicious day, a teacher or monk who has performed the proper fasts, ceremonies, visualizations, and prayers writes them out. The words must flow along a single line for as long as necessary, following special grammatical rules. Other lines may be added, with the order following specific principles. These long strips of writing are done very meticulously and are then carefully checked for accuracy. In addition, a “correction” mantra is added to counteract any mistakes that might have occurred. At the end of each writing is a mantra that seals it with the power of truth, and special wishes are added to conduct the flow of energy in a certain way. The writings are carefully placed in the proper parts of the statue. A closing rite then fully activates the energy of the mantras and precious objects. Tarthang Tulku also mentioned that it is considered especially important that large statues receive this empowerment once a year to renew the blessings and purify the consciousness of its worshipers. In Tibet, large groups would at times gather together to perform this ceremony for many statues at once. Sometimes great masters would travel hundreds of miles to attend such ceremonies, which were often dedicated to special purposes such as world peace or removing all suffering in the world. The main purpose of repeating the consecration ceremony on occasions other than the original completion of the work is to increase the holiness of the image and renew observances of respect toward it. The reconsecration would most likely take place for a special event, such as the inauguration of a temple or to celebrate a particularly holy day. For reconsecration the face might be repainted, and the pigment in the eyes, lips, and hair redelineated, especially if they have become worn or damaged with use. If the mantras are to be renewed or if the image is to be regilded, the objects previously installed may be temporarily removed (Kazi 1966, 10). A statue would also be reconsecrated after being desecrated by flood, fire, violence and war, or other calamities. If possible the original contents would be reinserted, but if some or all were found to be damaged they would be augmented or replaced with new objects (Aye Tulku, Lobsang Nyima 1989). 3 OPENING OF STATUES AT THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART3.1 BACKGROUNDTIBETAN STATUES have at times been opened in museum conservation laboratories or by private collectors, and the consecrated objects have been removed for scientific or art historical study or simply to see what is there. The goal has sometimes been to help Scholarly considerations begin with the identification of the wide range of objects that have been found inside statues. Beyond identification may be more in-depth art historical or technical studies of the objects. The major conservation issues are to determine how much damage opening a piece will entail and whether the results will be worth the permanent change. Another problem to be considered is how fragile objects removed from the piece, such as disintegrating paper scrolls, will be handled and stored. Equally important to the conservator are the ethical issues, since in a museum the conservator generally makes important contributions to the final decision about whether a consecrated statue should be tampered with and usually opens the piece. The primary ethical questions involved are whether opening a statue will desecrate it in the eyes of the practitioners who made and used it and in the eyes of their descendants, whether we should care if they consider the opening a desecration, and whether the information to be gained justifies any desecration. These ethical issues are discussed in section 4, which reports on the viewpoints of living practitioners. The types of objects encountered when studying consecrated statues are illustrated in this section, with a discussion of pieces that have been opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 3.2 MATERIALS AND METHODSDuring a six-year regional provenance study of 340 Himalayan statues from several museums and private collections (Reedy n.d.), all pieces were examined for physical evidence relating to a consecration ceremony. One hundred sixty-nine of the 340 statues are solid, so they could never have had interior contents. The 171 hollow-cast pieces were studied through surface examination and x-ray radiography to identify the presence of any remaining interior contents. Many hollow statues with no contents also have no bottom baseplate. All most likely once contained objects that were removed along with the baseplate. Some statues that are missing a baseplate still have bits and pieces of their former contents adhering to the interior walls of the piece or lodged in the top of the head. For those statues it is thus possible to identify and list at least some of the types of objects they once held. As part of the provenance study, two statues, one belonging to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and one from a private collection, were opened for a thorough study of the contents. Subsequently, six more statues from the museum's collection were opened at curatorial request, some of which were part of the provenance study and some of which were not. Prior to the provenance study, two other museum objects had been opened; one other object had arrived at the museum already opened, and although the accompanying contents were said to have been removed from that piece, there was no documentation to prove it. The contents from the 10 documented openings will be discussed in detail here and compared with the contents from several pieces that were opened elsewhere and documented. 3.3 MODE OF INSERTIONContents were almost always inserted from the underside of the piece, and the statues were then sealed by an unalloyed copper plate set into the bottom rim of the base (fig. 1).

Twenty-nine statues in the provenance study have a hole or plugged-up hole on the back, which sometimes might have been used to place contents inside (fig. 2). Dagyab (1977, 1:33) reported that although sacred objects are usually placed inside a piece through a lotus base, statues without a lotus seat have openings on the back through which objects are inserted. In the provenance study we found that not all statues with back holes have interior contents or evidence that contents were once present; other statues have both a back hole and a lotus base.

However, in some cases objects could only have been placed inside a piece though the back hole. For example, a Tibetan image of the great female teacher Ma-chik Lab-kyi Dron-ma was found to be filled with organic material in the upper portion of the figure. Although the base is hollow, the legs are solid. Since there are no other holes in the object, and the organic material is not part of the remains of a clay core, it must have been placed inside the piece through the hole at the center of the back. In other statues, some but not all of the objects may have been placed inside through the back hole, with the remainder of the objects being inserted through the underside of the base, which was then sealed by a copper plate. One west Tibetan seated Buddha image has both a back hole and a hollow base, with many objects placed inside the piece. A small metal statue found inside is too large to fit through the back hole and must have been inserted through the base. However, many other smaller objects found inside could have been inserted from the back. In some cases an outline of a hole is chiseled onto the back, but the marks do not completely penetrate the metal. A few solid-cast pieces had a large back patch that has now fallen off, but obviously no contents were actually inserted into a solid statue. For these cases, the purpose of the back hole is unclear. It is possible that this feature was meant to provide the appearance of a statue containing consecrated objects when in fact none were placed inside; or perhaps objects were inserted through the base but for some reason the participants in the ceremony wished to have it appear that they were placed into the back; or the outline may just be a stylized rendering of a ceremonial practice. 3.4 RESULTSThe interior contents of the 10 objects opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art are summarized in table 1. The contents of the two opened as part of the provenance study are described in detail, and highlights of the remaining ones are elaborated on. Information obtained through surface examination and x-ray radiography of additional objects is also discussed. TABLE 1 Interior Contents of Objects Opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art 3.4.1 Contents of a West Tibetan Buddha ShākyamuniDuring examination of a seated Buddha Shākyamuni image in the style of 12th- to 13th-century west Tibet, x-ray radiography revealed that the piece contained a small metal object that appeared to be a four-faced seated Buddha statue. In light of the possible importance of the small statue, we chose to open the piece for further study of the contents. The statue had been sealed at the base in an unusual manner, with five separate copper plates riveted together rather than the usual single copper plate. The objects conservator could therefore open it with minimal damage, as the removal of only one copper plate by grinding down four rivets was all that was necessary to remove the contents. After removal of that plate, the first layer encountered was a deteriorated silk textile tucked over the bottom of the statue's contents. Behind the silk piece, a four-faced metal Buddha image was found lying upside down, wrapped in silk cloth, and placed within a large amount of sawdust mixed with twigs from a coniferous wood. A 10-gram sample of sawdust was used for carbon-14 dating at the UCLA Radiocarbon Laboratory (UCLA-2533), which provided a date of 1420 A.D. � 45 years. This date may represent the final sealing of the piece, assuming that the sawdust was not from very old wood and that it all originated from wood of one age. The small copper-based image represents the deity Sarvavid Vairocana, for which metal images are extremely rare. The meditation of Sarvavid Vairocana was especially popular in the west Tibet region during the medieval period, and it is practiced even today in the Tibetan refugee communities. The purpose is to help one attain rebirth in fortunate circumstances, and it can be done either to benefit oneself or others (Getty 1962, 34; Clark 1:1937, 125; Tucci 1935, 30–42). X-ray radiography of this small statue showed that it too was hollow cast and probably has sacred objects sealed within it. The surface of the piece is very worn, indicating that when the outer piece was sealed in the 14th or 15th century, the Sarvavid Vairocana image had already been in use for some time. Due to its stylistic similarity to images found in 11th- to 12th-century west Tibetan monasteries such as Alchi and Ta pho, it is possible the piece might date to that period. Because the carbon-14 date indicates the piece might have been last sealed in the 14th or 15th century, and stylistically the outer image is 12th to 13th century while the inner piece is of that age or older, it is possible that the current contents are in part the result of a reconsecration. Additional support for the idea of a consecration performed after the original casting comes from the surface examination of the statue. The outer Buddha image is technically a sophisticated work of casting, but the five-piece baseplate and its many rivets is of much lesser craftsmanship. It seems most likely to be the work of people who were not located in a major casting center and who were using any small pieces of copper they had on hand. It is highly unlikely that the image was put into use after manufacture without being consecrated and filled with objects at that time. The original contents may have been a mixture of the current ones, or the piece may have contained an entirely different set of objects that were for some reason removed at the time it was reconsecrated in the 14th or 15th century. Included with the Sarvavid Vairocana were 11 terracotta images of deities (called ts'a ts'a, representing the body of the Buddha), all consistent with a west Tibet provenance of indeterminate date. They range from 3.8 to 4.1 cm in height, and four are covered with a fine powdered whitewash. Nine have features that survived well enough to permit identification of the deities depicted. Two ts'a ts'a represent Padmasambhava, the legendary Indian tantric Buddhist teacher who traveled to Tibet in the eighth century and is considered a major force behind the establishment of Buddhism there. Another two are images of Shāntarakshita, the orthodox Indian pandit often associated with Padmasambhava and who was renowned for his monastic discipline and scholarship. The other ts'a ts'a represent several tantric Buddhist deities including Ushnīshavijayā (the goddess of long life), White Tārā, and Vajradhara. The process of opening the statue and a full illustration and description of the contents were reported elsewhere (Reedy 1986). We chose to reconsecrate the statue in a traditional Tibetan ceremony performed by a Tibetan Buddhist teacher living in Los Angeles. He placed new objects inside the image, and the reconsecration ceremony was intended to once again invest the statue with the power of the Buddha. 3.4.2 Contents of a Kashmiri-Style Avalokiteshvara ImageThe second statue opened as part of the technical study was a seated Avalokiteshvara in the style of 8th- to 9th-century Kashmir that was produced in either north Pakistan or Kashmir (fig. 3). It has a large hole on the back at the upper center of the lotus seat (fig. 4). Objects were visible through the hole, and these were removed for study. Some are wads of paper, and others are painted wood and bone pieces with string tied around them (fig. 5).

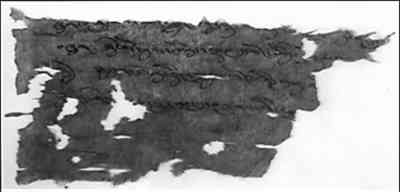

A paper conservator unrolled the wads of paper, revealing seven scraps with Tibetan handwriting in black ink, abbreviated and difficult to read (fig. 6). These scraps were encased in Mylar before study and translation.

The contents turned out not to be connected to the bodhisattva depicted and do not seem to be connected with a consecration ceremony at all. The largest fragment has references to the rules of spelling laid out by Ral pa can and a passage in which the writer asks someone to accept a turquoise that is all that was left by a destitute deceased person. Another fragment refers to an official with a Ladakhi title. A third has another reference to a deceased person or a corpse. One of the smaller fragments gives the name of a practitioner, dPal chen gLing p'i so cha 'dzin p'i srong Khol, or the life servant of the holder of the place of dPal chen gLing pa (Palchen Lingpa). Lingpa may be the great tantric teacher of Ū province in south central Tibet, who lived from 1128 to 1188 A.D. He was in charge of the monastery of sNa phur dgon and was the author of many tantric commentaries. In the 12th century his successor sent many disciples to north Pakistan, Kashmir, the Kangra Valley of north India, and elsewhere to live and teach (Roerich 1979, 659–69). Thus it would not be surprising to find a statue from Kashmir or north Pakistan containing writings by a monk from Lingpa's monastery. The Tibetan scholar Hugh Richardson has suggested that because all writing was considered sacred by Tibetan Buddhists and should not be destroyed, these scraps could simply be waste paper from monastery correspondence. The scraps could have been inserted at any time, and they are probably not connected with the original consecration of the statue. However, the pieces of wood and string probably were inserted during a consecration or reconsecration ceremony. 3.4.3 Pieces Opened Outside of the Provenance StudySeven statues and one ch�ten have been opened in the conservation laboratory at various times at curatorial request. Another ch�ten arrived at the museum already opened, accompanied by what were said to be its contents in a separate box. An image of the goddess Nairātmyā, opened in the most usual way by removing the one copper plate sealing the piece at the bottom, yielded a variety of objects such as bark, wood, bone, seed pods, many small tightly rolled paper mantra scrolls, and small bits of charcoal. There were also four small ts'a ts'a and two small clay stupas wrapped in textiles (fig. 7). The ts'a ts'a were red with a deity image in a contrasting tan color, two with the deity of wisdom, Ma�jushrī, and two with an as-yet-unidentified mahāsiddha(fig. 8). The two stupas, each with a carved design on the bottom (fig. 9), are intended to represent the mind of the Buddha. Also found was a larger terracotta ts'a ts'a originally wrapped in a textile and illustrating six deity images.

A statue of Padmasambhava was filled with many small paper scrolls tightly packed together. These scrolls remain in the paper conservation laboratory to be unrolled, but they appear to contain various mantras. A few small seeds were scattered among the scrolls. When an image of the teacher Karma Pakshi was opened, the first layer encountered was a textile with a rectangular piece of paper glued onto the center and covered with very faded Tibetan letters (fig. 10). Infrared photography was used to bring out the letters as much as possible (fig. 11), but they have not yet been fully identified and translated. Wrapped within the textile were: a round piece of carved bone with a geometric pattern and a hole on each side, a peach pit, a clove, a coral bead, a pearl, many small scrolls, a piece of blue silk, several pieces of wood, several large seed pods, a piece of shell, 13 bundles of scrolls, and a bundle filled with what appear to be cremation ashes.

For a statue of Sadakshari Lokeshvara, the contents consisted of chunks of wood with many twigs and leaves scattered throughout (all from a juniper tree). There were also a few bits of charcoal and 10 small stones (not precious or semiprecious, but ordinary stones such as schist, quartz, and sandstone), which were probably included because they were collected at a holy site. A portrait of a monk was filled with many carefully wrapped walnuts (fig. 12) in addition to the more usual textiles, seeds, wood, bark, scrolls, bone, ts'a ts'a, and stones. These walnuts might be objects particularly associated with that monk or with the primary location where he taught, or they might simply be objects that were in abundance at the site where the consecration was performed and were thus selected to finish filling the statue. Venerable Karma Gelek Yuthok suggested that walnuts wrapped in textiles could mean at least three things: the walnuts could have been blessed secret elements used and treasured by the deceased teacher; they might have been chosen as naturally pure and symbolic elements to fill the empty spaces in the statue; or the textiles they were wrapped in could have been pieces of the late teacher's or other high teacher's clothing (Yuthok 1989). Walnuts could also represent the head and brain and thus might have been appropriate symbols for a renowned scholar. Also found were a small lapis lazuli bead, a very small pearl, a piece of shell, three clay stupas, a small turquoise, a

One Bon-p� statue was opened, and inside were funerary items such as a bundle of black human hair, pieces of human skull, a human tooth, and packets of human bone. There were also five tightly rolled packets of small paintings, which are currently in the paper conservation laboratory waiting to be safely unrolled. In addition, we found packets of conifer twigs and many other tiny packets carefully wrapped in red and tan textiles. A west Tibetan image of the seated Buddha Shākyamuni, of a 14th-century style, yielded 11 tightly rolled paper scrolls with string tied around the bundles; Tibetan handwriting in black ink is visible. There are also small pieces of textiles, one red, one blue, one yellow, and one tan; three thicker textile pieces, one yellow, one gray, and one wrapped around what appears to be bone powder; two bundles of hair, one golden which may be animal hair and one brown which may be human hair; four small hard balls of white clay; two bundles of string; a small ivory piece (1.3�1.0 cm) with a design carved into the top in the shape of the numeral 1; and a small metal stupa (2.3�2.3 cm), hollow and itself filled with objects (disintegrating textile or paper). A ch�ten attributed to central Tibet of the 12th century was found to contain rolls of cotton, bones, a small twig, grain, sand, and paper with a faded design of figures. A 10-gram sample of grain was dated at the UCLA Radiocarbon Laboratory (UCLA-2535) and found to be less than 300 years old. Although it is possible the contents are newer than the ch�ten and are the result of a reconsecration during which objects were replaced, there was no evidence that the baseplate had been tampered with when the ch�ten was opened in the Conservation Center. Thus it is possible that the ch�ten may date to the 17th to 20th century, although it may be modeled after an earlier style. Another ch�ten attributed to central Tibet had been opened before the museum acquired it. The contents said to have been inside include 16 small clay stupas, two ts'a ts'a (Vajradhara and Ushnīshavijayā), two pieces of bone, cotton cloth, and barley seeds. A 10-gram sample of these seeds was dated at the UCLA Radiocarbon Laboratory (UCLA-2534) and found to be less than 300 years old, indicating that the ch�ten dates to the 3.4.4 Study by X-ray Radiography and Surface ExaminationObjects inside other statues in the Himalayan provenance study were examined as well as possible without opening the pieces. However, this examination provided very limited results. Only one statue besides the west Tibetan Shākyamuni image that was opened showed a metal object visible through x-ray radiography. An 11th- to 12th-century west Tibetan seated male figure, possibly a yogi, shows what appears to be a metal phallus loosely attached and now slightly off center inside the body (Reedy 1987, figs. 4–5). Its presence is probably related to tantric practices that may have been associated with this yogi. Since only interior metal objects are visible in radiographs, while the majority of consecrated objects are ceramic or organic materials, x-ray radiography is not a very useful technique by itself for studying the contents of sealed statues. However, it is possible that experimentation with other similar nondestructive techniques such as neutron radiography and industrial x-ray tomography might show them to be valuable for obtaining useful information without opening statues. Two of the statues in the study have the Tibetan syllables om ah hūm chiseled into the metal on the back of the piece (fig. 13). Although the consecration of paintings usually involves inscribing the back side with these sacred syllables, it is rare to find medieval period statues consecrated by this method. These syllables represent the three seed syllables respectively for the body, speech, and mind of the deities. They would most likely have been inscribed prior to the consecration ceremony, and their presence alone would not have made the image any holier. However, with consecration, these seeds are blessed and developed into the enlightened body, speech, and mind of the Buddha or deity depicted by the statue.

Surface examinations of the remainder of the 66 statues with consecration evidence permitted only a brief listing of the types of objects that appeared to be present. These objects included primarily textiles, plant remains, ceramic materials, and paper scrolls. 3.5 DISCUSSIONSeveral other museums and private collectors have documented the interior contents of Tibetan objects and reported finding similar types of items (Reynolds et al. 1986, 87–88; Preston 1983; Hatt 1980). This information accords well with what consecration texts say may be inserted. Many other pieces have been opened by curious collectors but the contents not properly documented. These sacred contents have provided only a limited amount of information about the works of art. The style of the objects inserted is sometimes, but only rarely, chronologically specific. Therefore, if the curator does not set aside funds for carbon-14 dating, the contents cannot provide a date of manufacture or sealing of the piece. An additional factor to consider regarding carbon-14 dating efforts is that casting core material almost always remains in the upper arms of consecrated statues and is usually carbon-rich from added organic temper. The new technology of accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) carbon-14 dating means that only a few milligrams of this material is enough to provide a date, and The west Tibetan seated Shākyamuni Buddha image, with some contents obviously worn and stylistically older than the outer Buddha image, but with carbon-14 dating of sawdust providing a later date than that to which the outer statue is stylistically attributed, is one example of the difficulties involved in dating a statue using interior contents. The two ch�tens with carbon-14 dates much different from their stylistic attributions are two more such examples. Similar problems are illustrated by a ch�ten opened elsewhere, whose contents were published in detail (Hatt 1980). That ch�ten from the Newark Museum collection, opened prior to its donation, was found to contain a variety of objects including textiles, seeds, manuscripts, drawings, animal hide, and small pieces of minerals and gems. The final sealing of the ch�ten could be dated to 1230 A.D. � 65 years by carbon-14 dating of barley seeds. However, some of the birchbark manuscripts were already quite old at the time of the 13th-century consecration, as they could be dated by orthographic peculiarities of the Tibetan script to the eighth or ninth century. Consecrated objects are also only rarely regionally specific. Technical studies of manufacturing methods, metal composition, and clay core composition of a Tibetan statue can usually provide better information about its place of origin than can consecrated objects (Reedy and Meyers 1987). Although the list of items found is indeed interesting, I would argue that we can usually derive as much useful information about the cultural and religious context of a piece through rigorous iconographic and stylistic studies. In addition, ethnographic and textual studies of Tibetan philosophies and practices have thus far only scratched the surface of the knowledge we can potentially gain about Tibetan works of art. Finally, a sufficient amount of money or time must be designated at the time of opening a statue for proper documentation of the objects recovered and their location within the statue, for translation of scrolls, and for an in-depth study of other objects recovered, or they will have been removed in vain. If adequate conservation resources (including large blocks of time) cannot be devoted to the proper treatment and storage of all of the fragile objects recovered, especially brittle, disintegrating paper, they are unlikely to be available to future scholars. 4 SURVEY OF TIBETAN PRACTITIONERS4.1 MATERIALS AND METHODSAFTER HAVING observed the opening of a number of consecrated statues and recording their interior contents, I decided to research the question of how Tibetan Buddhist practitioners really feel about the opening of these statues, to assess more accurately the ethical issues involved. I prepared a survey and sent it to 18 prominent Tibetan religious teachers in India, Nepal, Canada, and the United States. Many of the 10 answers I received were quite elaborate, and the Tibetans obviously were concerned about this issue. Some had already thought about the problem at length on their own and were happy to share their viewpoints with the museum. The primary questions concerning consecration included in the survey were:

4.2 RESULTSTable 2 lists the respondents and their affiliations. Because many of the answers were so detailed and because not everyone answered all of the questions and some wrote on additional topics, the responses cannot easily be converted into table format without risking some misrepresentation. The responses are therefore discussed below, organized according to general topic rather than strictly by respondent. TABLE 2 List of Consecration Survey Respondents None of the Tibetan leaders were comfortable with the opening of statues in a museum context. Two felt, however, that it was not a complete desecration. The others held strong opinions that statues should never be opened for museum study. Venerable Karma Gelek Yuthok, deputy secretary of the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, prepared an extensive paper on the subject for the council's reply. In it he says:

∗Respondents to the consecration survey are listed in table 2. All references in this section are to letters to the author from the survey respondents, 1989. His Holiness Sakya Trizin replied that a Tibetan Buddhist would avoid opening a consecrated statue unless there was a very important reason, such as the need to disassemble or move a statue during the renovation or repair of a temple. In such cases specific rituals are performed before the contents are removed, and the image must be reconsecrated after they are placed back inside. Aye Tulku, Lobsang Nyima, began his response by stating that since religious objects are extremely sacred to the Tibetans, he hoped these objects would always be handled in the museum with the utmost respect and care. Although it would technically be a desecration to open a sacred statue, he felt that there would be no harm in opening non-tantric statues provided that the object of the research is to further knowledge and ultimately benefit everyone by helping to preserve the sacred teachings. These statues should only be opened with the pure motivation of preserving and furthering the knowledge gained from researching the contents. Extreme care and respect should be used with any opening procedure. Tantric images contain mantras relating to the deities, and the proper initiations should be undertaken in order to read and understand them. Geshe Thubten Gyatso felt that since it seems to be the custom in this country, then opening a statue would not be a desecration. If the piece is opened with good intentions to investigate the contents then there would be no fault. According to the Sakya Monastery in Seattle, led by His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Sakya, the improper opening of a consecrated statue in any setting is a desecration. Such an act is nonvirtuous and according to the law of action and result will cause harm to the instigator (i.e., the curator making the request) as well as to the person who actually carries out the desecration (i.e., the conservator). Furthermore, the performance of this nonvirtuous act diminishes the stock of merit of all beings. Opening a statue is the converse of a consecration ceremony, which is beneficial and creates merit for those immediately concerned and for society as a whole. According to Tarthang Tulku, Head Lama of the Tibetan Nyingma Meditation Center in Berkeley, California, sacred statues have a special meaning and value higher than artistic beauty because they are bearers of blessings and inspiration. The blessings of the statue disappear if the inner contents are removed, so from a traditional point of view the deity has been destroyed. He concludes with, “If you ask my opinion, I find it hard to give you direction that will accommodate the Western view of these matters, which is very different from the traditional Buddhist understanding. So the best I can do is inform you of the traditional perspective and you can judge for yourself how to proceed.” According to Thubten Jigme Norbu of the Tibet Society, before consecration the statue is just like dirt. After consecration it is a symbolic representation of Buddha himself. In his opinion, opening a statue for scientific or art historical study is a terrible thing—“like tearing out the guts of living beings.” The Venerable Karma Gelek Yuthok described an acceptable opening procedure used only when a statue is in need of renovation due to damage or when an exclusively religious reason arises to open it. The Buddha or deity (in subtle spirit form) imbibed by the statue at consecration is formally requested through the medium of a capable Buddhist priest to leave the statue during a short ritual called gshegs-gsol (pronounced shey-sol, meaning “request to leave”). When the repair work on the statue is completed and the contents are reinstalled, care must be taken to place everything correctly, especially the mantra rolls, which may appear identical on the outside, but contain different mantras. Different parts of the body receive different mantra rolls. Venerable Yuthok notes that since different sets of mantra rolls were originally consecrated as different organs of the deity depicted by the statue, misplacing them would be like a surgeon misplacing organs during an operation. One acceptable opening procedure described by the Sakya Monastery of Seattle (called a chog and pronounced “a choke”) is used in Tibet when statues must be repaired. In a special ritual involving a mirror, the blessing the statue receives when consecrated is transferred to the image in the mirror. When the work on the statue is completed, the blessings are transferred back from the mirror image to the statue, which should then be reconsecrated within a month. The Sakya monastery also emphasized that it is important that conservators and scientists who work with Tibetan Buddhist objects show respect for the image as a religious object so that the practitioners will not be offended or upset by the treatment accorded the object in the museum. For them, this means that the image should be treated with care, kept in a clean area, not put on the floor or stepped on, and kept slightly elevated if possible. 4.3 DISCUSSIONIt is clear that for the most part Tibetans see the opening of a statue to be a desecration of holy objects and an offense to their beliefs. Under normal circumstances a Tibetan statue would not be opened except for repairs or if a large statue had to be disassembled and moved. Even then, the consecrated objects would not be disturbed unless necessary, and the pieces would always be reconsecrated when the work was finished. Only qualified religious persons opened such statues, and they followed a prescribed ceremony and procedure. The Tibetans are not militantly demanding that statues be left sealed; they leave that decision in the hands of the current owners. Yet most have made it clear that, to them, the special blessings and religious qualities of a statue are essentially destroyed once a piece has been opened and the consecrated interior objects removed. 5 CONCLUSIONSA REVIEW of the results of past statue openings shows that in fact very little useful information is gained, however interesting the statue contents may be. At the same time, the Tibetan feelings are strong that the sacred nature of a statue is defaced if the contents are removed. It is my opinion that these feelings should be taken very seriously, for several reasons. First, Tibetan Buddhism is not a dead religion, and this is not a case where the present practitioners are far removed in descent from the people who originally made and used the objects. Therefore, when they talk about museum statues, they are talking about a group of objects some of them may have actually used in worship in the monasteries of Tibet. Second, we know from historical and ethnographic sources that these sacred statues were never discarded in Tibet in the past but remained forever within the monastery walls. When they became too worn or damaged for ritual use, they were housed in special shrines where they continued to be treated with respect (Snellgrove 1978, 351). The presence today of so many statues in Western museums and private collections is not due to their being willingly sold or discarded by the previous Tibetan owners, but is directly attributable to the relatively recent Chinese invasion of Tibet and the subsequent destruction of a large percentage of its monasteries and the death or uprooting of many practicing Tibetan Buddhists. Finally, the refugees in India, Nepal, and the West have worked very hard to overcome enormous obstacles and maintain their religion and culture outside of Tibet. We would have to be able to point to great advances in knowledge to be gained by desecrating their sacred objects through opening them in order to even begin to justify that practice. The previous openings of statues have afforded us an opportunity to document the types and range of objects they may contain. We now have data to compare actual contents with textual and ethnographic descriptions of what the contents should comprise. The question to address now is: Should we open any more statues for study of the interior contents? Although each conservator must decide how to handle curatorial requests, it is my opinion, after reviewing the evidence, that these statues should not be tampered with and that instead, more effort should be expended to find alternative art historical and scientific methods for obtaining the desired information about the history and context of Tibetan bronzes. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTHE RESEARCH and writing of this paper were carried out while I was an associate conservation scientist at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Conservation Center. I am grateful to several colleagues for their help. Billie Milam, while senior objects conservator there, and Steve Cristin-Poucher, objects conservator, opened the statues with great care. Victoria Blyth-Hill, senior paper conservator, handled all of the paper objects recovered and prepared them so they could be safely studied. All photographs were taken by John Gebhard and Adam Avila of the Conservation Center. Rainer Berger from the UCLA Radiocarbon Laboratory provided the carbon-14 dates. Pieter Meyers, in numerous discussions about these pieces, had many insightful suggestions. Terry Reedy made suggestions regarding the organization of the paper that resulted in significant improvements in clarity. I also wish to thank all of the Tibetan teachers who kindly took the time to respond to my questionnaire. An earlier version of this paper was presented in the General Session at the 17th annual meeting of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Cincinnati, 1989. REFERENCESAyeTulku, LobsangNyima. 1989. Letter to author. Clark, W. E.1937. Two lamaistic pantheons. 2 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dagyab, L. S.1977. Tibetan religious art. 2 vols. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. Getty, A.1962. The gods of northern Buddhism. [1928] Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle. Gyatso, J.1986. Images as presence: The place of art in Tibetan religious thinking. In V.Reynolds, A.Heller, and J.Gyatso, The Newark Museum Tibetan collection III: Sculpture and painting. Newark: Newark Museum. Hatt, R. T.1980. A thirteenth century Tibetan reliquary. Appendix by W. T. Chase, I. V. Bene, and L. Zycherman. Artibus Asiae42(2/3):175–220. Kazi, S. T.1966. Second exhibition of Tibetan art. New Delhi: Tibet House Museum. Panchen �trulRinpoche. 1987. The consecration ritual (rabney). Ch�-yang1(2):53–64. Preston, D. J.1983. Spilled beans and secret scrolls. Natural History92(4):96–99. Reedy, C. L.1986. A Buddha within a Buddha: Two medieval Himalayan metal statues. Arts of Asia16(2):94–101. Reedy, C. L.1987. Tibetan art as an expression of north Indian tantric Buddhism. In Himalayas at a Crossroads: Portrait of a Changing World, ed.D.Shimkhada. Pasadena: Pacific Asia Museum. 35–60. Reedy, C. L. n.d. Himalayan bronzes: Using technical analysis to determine regional origins. Pasadena and London: Pacific Asia Museum and Robert G. Sawers Publishing, forthcoming. Reedy, C. L., and P.Meyers. 1987. An interdisciplinary method for employing technical data to determine regional provenance of copper alloy statues. In Recent advances in the conservation and analysis of artifacts, comp. J.Black. London: Summer Schools Press. 173–78. Reynolds, V., A.Heller, and J.Gyatso. 1986. The Newark Museum Tibetan collection III: Sculpture and painting. Newark: Newark Museum. Roerich, G. N.1979. The blue annals. [2d ed 1947] Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. SharpaTulku, and M.Perrott. 1985. The ritual of consecration. Tibet Journal10(2):35–49. Snellgrove, D.1978. The image of the Buddha. Paris: UNESCO. TarthangTulku. 1989. Letter to author. Tucci, G.1935. Indo-Tibetica 2, pt. 1 (Tabo). Rome: Reale Accademia d'Italia. Tucci, G.1949. Tibetan painted scrolls. 3 vols. Rome: La Libreria Dello Stato. Yuthok, Ven. K. G.1989. Letter to author prepared for the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs of H. H. the Dalai Lama. AUTHOR INFORMATIONCHANDRA L. REEDY is an assistant professor in the Art Conservation Program of the University of Delaware and coordinator of its new Ph.D. program in art conservation research. She was previously employed as a scientist at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Conservation Center. She received her graduate training at the University of California, Los Angeles, where she received her Ph.D. from the interdisciplinary Archaeology Program with specializations in materials analysis of art and archaeological objects and in the South Asian region. She has done fieldwork in north India and maintains research interests in the history of Tibetan art, material culture, and religion. Address: Art Conservation Department, University of Delaware, 303 Old College, Newark, Del. 19716.

Section Index Section Index |