THE ROLE OF CONNOISSEURSHIP IN DETERMINING THE TEXTILE CONSERVATOR'S TREATMENT OPTIONSPATSY ORLOFSKY, & DEBORAH LEE TRUPIN

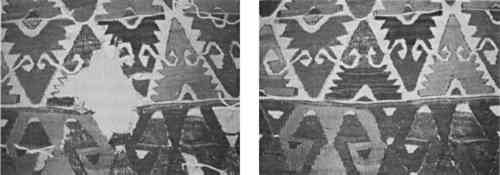

3 TYPE OF TEXTILE COMBINED WITH CONNOISSEURSHIP DETERMINES TREATMENT OPTIONSIn recent years the authors have observed three combinations of subgroups and elements of the connoisseurship bias that interact in the selection of treatment options. In the first combination, religious, archaeological, and ethnographic textiles and textiles that serve primarily as historical documents seem to be affected chiefly by awe and by changing cultural significance. Second, the pressure to recapture original appearance and marketplace forces have gained a greater influence over the treatment of rugs, tapestries, upholstery, Navajo blankets, quilts, woven coverlets, and needlepoint. Third, and finally, the influence of the owner and the concerns of aesthetics tend to guide solutions for costumes and a range of domestic textiles. Let us examine the role of awe and changing cultural significance in a conservator's choice of treatment options. As illustrated by the Shroud of Turin, awe probably plays the strongest role in religious and reliquary objects, such as fabric fragments from holy crucifixes. These reliquary textiles have had powerful auras and carry with them the expectation of immunity from trespass. Relic veneration exists in all centuries, and examples can be found from every country. Awe severely limits a conservator's options; it is the greatest inhibitor of choice. Sometimes religious textiles like a saint's tunic have come to be considered so precious that their dust is not seen as detritus but as treasure. It seems to follow that the greater the awe with which the conservators behold the textile object, the more likely they are to preserve every stain, thread, and historic dirt particle. In such cases, all concerned instinctively recoil from intrusive treatment because they understand that any action may negatively affect the future significance of the object. The shifting perception of the significance of archaeological and ethnographic textiles combines with awe to influence a conservator's approach. In the past, when awe was not as great a deterrent to conservation treatments, conservators routinely used to wet-clean and mount archaeological and ethnographic textiles. It was felt necessary to clean these pieces and stitch them to stable supports. For some textiles, it also was considered essential to be able to observe every detail for study purposes, even to the extent of unwrapping mummy bundles. A mummy bundle would not be taken apart today but would be preserved undisturbed and packed in archival materials. What has caused these changes in approach? In part, we already have enough mummy bundles that have been taken apart, so we are not driven by the curiosity and voyeurism of the past. But, looking more broadly at the range of archaeological and ethnographic textiles, we now realize we must treat objects from all cultures with Most textile conservators now consider only preventative conservation in the form of passive mounts, developed in a variety of creative styles, and upgraded storage for archaeological and ethnographic pieces. It is hard for the textile conservator to justify elaborate sewing on these pieces, let alone incorporating any restoration work. Indeed, if anything, the trend in this area is toward the limitation rather than the development, of options. Changing attitudes toward cultural significance also limit the treatment options for historic document textiles and cultural icons, such as a Nazi banner or a Ku Klux Klan robe and hood. Invasive treatment is no longer considered appropriate for textiles of unique significance. Swatches from a sample book generally are not removed to be treated separately because it is the composite nature of such an object that expresses its value. For these textiles, as for religious, archaeological, and ethnographic pieces, it is universally acknowledged that overambitious treatment may prejudice artistic or cultural significance. The fabric hair ribbon or tutu of the Degas dancer statue would not be removed or replaced (1d). The character of a Mir� scroll would not be changed by electing to alter the mounting technique. When faced with rugs, tapestries, upholstery, Navajo blankets, quilts, woven coverlets, and needlepoint, the dominant aspects of the connoisseurship bias are the striving for original appearance and the forces of the marketplace—the second combination (fig. 4). In contrast to the first combination, where the connoisseurship bias limited active treatments, for these subgroups of objects the bias promotes a wider range of more intensive treatments. Connoisseurship, traditional care, and the construction and condition of these objects combine to permit a range of aesthetically pleasing treatments, including ethical restoration. Indeed, there is a long-standing subculture of restoration in these subgroups that conservators have recently begun to reincorporate into their treatments.

Just as in other conservation disciplines, tremendous suspicion of the traditional restorer had developed in textile conservation. In fact, the race to distance conservation from restoration became a strong characteristic of our field from the 1960s to the mid-1980s. In the last five years, however, the contribution of the gifted craftsperson-restorer has been re-evaluated. The received wisdom traditions of an earlier era are now understood to contain elements of real artistry and empirical knowledge that must not be lost. These skills, which restorers have practiced all along, are now being validated and legitimized for certain subgroups, especially as they are being combined with thorough documentation of treatments. While the dual forces of the marketplace and the desire for original appearance have had a strong impact on textile conservators' move to embrace restoration techniques, it should also be noted that the interest in Tapestries have been “approved” for restoration because they have always been closely associated with painterly images; their main value is often their pictorial impression. In addition, tapestries are considered strong enough to withstand the rigors of restoration, and they have a long-standing restoration tradition (more than 300 years in signed repairs and more than 700 years in documented inventories). However, not all tapestries are or should necessarily be restored. Some receive other treatments such as darning or “space-stitching,” patching, strapping, or lining, for reasons of condition, aesthetics, or budget. This range of restorative treatments also exists for quilts, Navajo blankets and rugs, but for these textiles the desire for restoration is motivated and bolstered not by the pictorial image but by a well-informed collectors' market. Although the marketplace may have a full range of pieces, from those in perfect condition to those in fragments, there is a large middle ground of extremely valuable but not necessarily rare examples for which acceptance in the marketplace requires that they look nearly perfect. People have very strong reactions to certain damaged textiles. Interviews with auctioneeers, antiquarians, and dealers indicate that many collectors do not want to make decisions about or excuses for condition; their desire is for flawlessness. Thus, while certain museum textiles can be granted a special license against invasive treatment, permitting them to remain in their present condition even if that condition appears Concerns about appearance also promote restoration of coverlets and needlepoints. The grosser weave structure of these pieces makes restoration possible. Interestingly, many restorers and conservators now feel that restoration may not necessarily constitute more intervention than conservation and that restoration of coverlets and needlepoints may actually make them more structurally sound. However, even when conserved rather than restored, current standards require the patch or support to be more cosmetically integrated than did the aesthetics of a decade ago, when we simply applied a cotton patch behind a loss. Today, a hole in a coverlet will either be completely rewoven or have a separately woven patch worked into the fabric. The first two combinations of subgroups and elements of the connoisseurship bias have demonstrated two treatment extremes; on the one hand, the limitations imposed by awe and shifting cultural significance and on the other, the urge to restore brought about by instinctive concerns for original appearance and the forces of the marketplace. The results of the third combination are not as clear cut. For costumes and use-oriented household and domestic textiles, the treatment plan must incorporate the owners' needs and the issues of aesthetics and patina. The result is usually a balancing act that requires the textile conservator to have a large repertoire of ethical conservation tactics. Museums set standards for their textile artifacts to reflect their function as the custodians and interpreters of cultural heritage and as the public trust for scholarship and preservation. But the textile that decorates the home or is used in family rituals is still in the midst of its useful life and has not yet been removed to be preserved as a symbol. Consequently, it is not uncommon that certain textiles are brought to conservators with the demand that they be made to look new. In many of these cases, restoration is not an option because the physical structure of these textiles does not permit it. Cleaning and stain removal techniques and traditional sewing methods like fine darning are more appropriate. The desire for newness and perfection is also driven by the present vogue among private clients for artificial period settings. Perfect textile props are required to enhance the experience of being in these stage-set like rooms, interior-designed re-creations of a fantasy time gone by. Paisley shawls must have vibrant colors and intact fringe. Antique bed linens must be pristine. Laces, hand towels, and tablecloths can have no discolorations or holes. Even a tiny stain can be unacceptable. Conservators receive requests for controlled bleaching, which they sometimes carry out for wedding veils and lace tablecloths. Even parasols and dolls clothes are not exempt from the perfection bias. At the same time, there is a growing awareness that some objects may be enhanced by their patina. We concede a considerable Damage in costumes can also be difficult to reverse and, like treatments of other domestic textiles, costume treatments are influenced by the wishes of their present owners or the significance of their former owners. For years, the most extensive sort of refashioning was practiced on costume. Today the chief reason to engage in a full-scale reconstruction would be to present the aesthetics of a certain period with historical accuracy. There are also an increasing number of costumes whose conservation needs are answered with very limited treatment. The immigrant's dress is not made beautiful for the Ellis Island Museum. A quirky alteration in the sleeve of a First Lady's gown is preserved because historic photographs date the alteration. Costumes drawn from popular culture are not reworked because they hold us fast to a particular moment in time. |