19TH-CENTURY PORTRAITS ON SCORED PANELS IN THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ARTCHRISTINA CURRIE

ABSTRACT—Many American portraitists chose to use textured panels for portraits in the first half of the 19th century. The author examined eight 19th-century portraits on panel in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art dating from between ca. 1810 and ca. 1832 and produced by the following artists: Gilbert Stuart, Wesley Jarvis, James Frothingham, Matthew Harris Jouett, Samuel Lovett Waldo, and the partnership of Waldo and William Jewett. The author relates the results of her technical analyses of these portraits and then focuses more closely on the panels of Gilbert Stuart, including those found in other collections. 1 INTRODUCTIONMany American portraitists working on wood panel in the first half of the 19th century created an intentionally textured surface. This practice was discussed by Goldberg (1993). During technical examination, similar scoring patterns were discovered on all eight of the 19th-century portrait paintings on panel at the Cleveland Museum of Art. The panels are dated between ca. 1810 and ca. 1832. The six artists represented are Gilbert Stuart, John Wesley Jarvis, James Frothingham, Matthew Harris Jouett, Samuel Lovett Waldo, and the partnership of Samuel Lovett Waldo and William Jewett. Technical examination of these paintings clearly proves that there was no set formula regarding wood type or scoring pattern. An assessment of whether or not scoring was applied directly into the panel or into the ground layer was made based on the technical evidence. Observation of a large range of scored panels by Gilbert Stuart in other collections revealed many variations in his scoring patterns. An early dated example suggests that Stuart may have started the fashion for the technique. 2 WOOD IDENTIFICATIONWood identification was carried out on those panels where it was possible to take a sample (table 1). True mahogany (Swietenia sp.) was found in three cases, tulip poplar (Liriodendron sp.) in two, and linden (Tilia sp.) in one. TABLE 1 (a) Samples were analyzed by Harry Alden, botanist at the Center for Wood Anatomy Research, Forest Products Laboratory, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Madison, Wisconsin 3 SCORING PATTERNSThe scoring patterns are invariably linear in character but differ in their direction, fineness, evenness, and spacing. The scoring lines in Jarvis's Thomas Abthorpe Cooper(fig. 1) are confined to the face, collar, and background. In all other Cleveland panels examined, the pattern covers the entire front surfaces. Three panels—Thomas Abthorpe Cooper, Stuart's Mrs. James Stuart (ca. 1815, Cleveland Museum of Art), and Frothingham's Samuel Barber Clark(fig. 2)—display diagonal scoring patterns running from the upper right to the lower left. The scoring in Waldo's Independent Beggar(fig. 3) follows the opposite diagonal. Both Jarvis's Benjamin Rouse(fig. 4) and Waldo and Jewett's Portrait of a Man(fig. 5) have linear scoring in both diagonals. However, the scoring in Portrait of a Man is so fine that it merely imparts a slight matte quality to the painting surface.

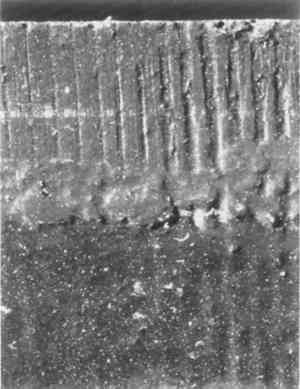

The nature of the pattern in this case is distinguishable only in the x-radiograph. The purpose of the scoring probably had more to do with “tooth” than with decorative effect. Jouett's Thomas Hart Benton(figs. 6, 7) is the only example displaying vertical incised lines.

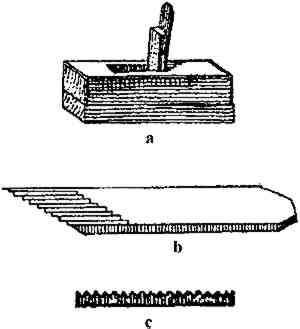

The linear incisions usually appear in groups indicating the width of the tool used, as, for example, in Benjamin Rouse (see fig. 4). This tool would have been either a plane held by two wooden handles or, more likely, a toothing plane consisting of a serrated blade held within a wooden casing (fig. 8), the blade measuring about 2–3 cm in width. Unlike the straightedged blades of ordinary planes, the serrated blade of the toothing plane was held in place almost vertically, and the wooden casing was a little shorter. Eric Sloane, in A Museum of Early American Tools (1964), illustrates an advertisement from the 1800s offering a wide selection of planes for carpenters, coopers, and cabinet and coach makers. Included in the advertisement are tooth planes, available in case steel for $1.25.

The use of a toothing plane for scoring the front of panels was a secondary application. Its more common use was the preparation of wood surfaces before joining or adding veneer. A typically “twilled” wood panel by Gilbert Stuart, William Codman (ca. 1812, private collection), provides evidence of this joining technique. Stuart's studio extended the panel, the additions clearly having been painted by the same hand. The joins are supported on the reverse by shallow wooden battens. The visible parts of these battens display a fine network of scoring in both diagonals, and there are traces of scoring lines on the original panel adjacent to the battens. Although it is impossible to see the inside of the join, the evidence suggests that the panel maker scored both the inside edges of the 4 APPLICATION OF TEXTURE: INTO PANEL OR GROUND?Scoring patterns were either applied directly to the panel support or added after the ground layer was applied. To distinguish between the two methods, the paintings were examined with ordinary light, under magnification, and with x-radiography. In most cases, it was then possible to deduce the source of the pattern (table 1). In most paintings, the visibility of the wood grain as white markings in the x-radiograph indicates a significant lead content in the ground layer. By the same principle, deliberate incisions made into the panel itself prior to priming become prominent in the x-radiograph as sharp white lines, such as the diagonally scored lines in Samuel Barber Clark (see fig. 2) and Portrait of a Man (see fig. 5). These white lines appear to have more contrast and are more clearly defined in the x-radiograph when the overlying paint layers are dark and do not contain significant proportions of lead white. If the incised lines appear dark and soft-edged in an x-radiograph where the wood grain is visible as white markings and the ground as whitish brush In some paintings, areas of paint and ground loss provide evidence of scoring before groundlayer application. In Thomas Hart Benton, the top and bottom 1.1 cm of the panel were never primed (see figs. 6, 7). The paint layer, however, extends to the edges of the panel. With x-radiography and the naked eye, the vertical scoring pattern is clearly visible across the full length of the support. The incised lines appear much sharper on the 1.1 cm of the top and bottom edges where they have not been softened by an overlying lead white–based ground layer. Ambiguities in interpretation do occur, especially when the scoring lines are of a similar width to the spaces between them. An example is Mrs. James Stuart. In the x-radiograph, the visible wood grain indicates a lead white–based ground (this x-radiograph is not illustrated, because a supporting cradle confuses the image). In certain places, the ground layer can be distinguished as broadly applied strokes. These strokes are cut through by dark lines, indicating that the scoring process occurred after ground application. Another confusing x-radiograph is that of Independent Beggar (see fig. 3). In this instance, microscopic examination revealed the presence of the wood support in some abraded high points of the scoring pattern, suggesting that the scoring pattern was applied to the panel directly before priming.

Benjamin Rouse (see fig. 4) presents a different problem. There is no clearly defined wood grain in the x-radiograph. Close examination of the painting's edges reveals abraded areas where the scoring is etched into the panel support. However, in another area of the edge, the exposed ground layer is physically separated by scoring lines as if the scoring had been applied after the ground. The x-radiograph shows the scoring pattern as thin, sharp white lines. On balance, it seems likely that the scoring was Of the 100 or more panel paintings by Gilbert Stuart that the author has seen, only a handful are not scored, including Henry Knox (ca. 1805, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Stuart's scored panels exhibit a range of linear pattern types that vary in direction, angle, and fineness of line. More often, his lines run in one diagonal or the other, although in some cases the panel has been scored in both diagonals, as in John Adams (ca. 1825, National Gallery of Art). Both Stuart's Egbert Benson (ca. 1820, New-York Historical Society) and Jarvis's copy of it (ca. 1820, New-York Historical Society) exhibit a light diagonal scoring pattern. However, in the Stuart original the incised lines run from upper right to lower left, while in the copy they run from upper left to lower right with occasional lines in the other diagonal. Past writers on Stuart asserted that he started to “twill” wood panels following Jefferson's embargo on shipping in 1807, when he experienced problems importing English twill canvas. Goldberg challenged this myth and gave many examples of scored panels after import restrictions were lifted (Goldberg 1993). This author would like to strengthen her case by supplying an example of a textured panel by Stuart securely dated seven years before 18071. Stuart's Horace Binney (1800, National Gallery of Art) is scored evenly in a diagonal direction from upper right to lower left (fig. 9). The x-radiograph, not sufficiently clear for reproduction here, shows groups of fine, soft-edged dark scoring lines indicating that the scoring was carried out into the ground layer rather than directly into the panel. These x-radiographic line characteristics are very similar to those in the x-radiograph of Jarvis's Thomas Abthorpe Cooper (see fig. 1). Stuart's preference for working on textured panels therefore evolved separately from the shortages of English twill canvases during the embargo. Stuart probably initiated the fashion for texturing panels around the turn of the century, but there are countless panel paintings in historical collections that must be examined first before drawing conclusions.

In European panel painting, the author has seen no examples of panels with incised linear patterns, the goal being to present as smooth a surface as possible. However, small random patches of scoring are sometimes noted in Flemish panel painting, such as an approximately 2 cm2 area of diagonal scoring in an anonymous Flemish panel painting, the 10th panel in a series of 16 illustrating the life and martyrdom of St. Victor (ca. 1510–20, Museum van Busleyden, Mechelen). These patches are certainly not intentional. They are more likely left behind after the rough leveling of the ground layer before it was smoothed down with a plant called pr�le (Mare's tail). Intentional texturing 5 CONCLUSIONSThrough this limited study of individual paintings, it is possible to appreciate the wide range of incised textures in 19th-century American portraits on panel. With the exception of Waldo and Jewett's Portrait of a Man, the scoring patterns examined are all clearly visible to the naked eye and serve a definite decorative function. There are variations in pattern and methods of application, even within the oeuvre of a particular painter. More data collection is necessary to establish the full extent of the use of this technique and whether Gilbert Stuart was the first to initiate it. Eventually, the examination of scoring patterns might be a useful tool in answering questions regarding attribution and authenticity. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe author would like to thank Marcia Steele, Kenneth B�, and Bruce Robertson for their consistent support and advice. Many thanks to Dean Yoder, who brought the Stuart panel William Codman to my attention and spent much time discussing the markings. Thanks also go to the others who helped in correspondence and discussion: Marcia Goldberg, Annette Blaugrund, Alexander Katlan, Mark Bockrath, Anne Hoenigswald, Ross Merrill, and Stephen Wolffe. Photography in this article is by Matthew Kocsis, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, except figure 9, which is courtesy of the National Gallery of Art. NOTES1. Franklin Kelly, curator of American and British paintings at the National Gallery of Art, informed me that Ellen Miles of the National Portrait Gallery recently found substantial documentary evidence to date the picture to 1800. REFERENCESGoldberg, M.1993. Textured panels in 19th-century American paintings. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation32:33–42. Sloane, E.1964. A museum of early American tools. New York: W. Funk. Storck, J. J. n.d. Le dictionnaire pratique de menuiserie, �b�nisterie, charpente. Paris. AUTHOR INFORMATIONCHRISTINA CURRIE received her M.A. in painting conservation at Gateshead Technical College, England, after obtaining a B.A. in the history of art from University College, London. She held internships at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University. During 1992–93, she was an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Cleveland Museum of Art, where she focused on the examination of the American painting collection. During 1993–94 she was an intern in the paintings workshop of the Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique in Belgium. She is now in private practice in Brussels as a paintings conservator. Address: Rue Victor Allard 50, bte 4, B-1180 Brussels, Belgium.

Section Index Section Index |