WOVEN BY THE GRANDMOTHERS: TWENTY-FOUR BLANKETS TRAVEL TO THE NAVAJO NATIONSUSAN HEALD, & KATHLEEN E. ASH-MILBY

ABSTRACT—As collaboration with Native peoples is increasingly expected of museums that house indigenous cultural materials, it is imperative that collections become more accessible to Native communities. The National Museum of the American Indian sent a selection of 19th-century Navajo blankets to the Navajo reservation in 1995 to develop an exhibition with community involvement and provide access for the community, especially weavers, to study the blankets. During the event, scheduled plans continually shifted due to unanticipated circumstances and, at times, mistaken assumptions. Ultimately, the success of the project—balancing access and preservation of the blankets—depended on the flexibility of museum staff to resolve issues as they arose. TITRE—Tiss�es par les a�eules: le voyage de vingt-quatre couvertures chez les Navajos. R�SUM�–Comme les mus�es qui poss�dent des collections ethnographiques sont de plus en plus requis de collaborer avec les peuples indig�nes, il devient imp�ratif que ces collections deviennent plus accessibles aux communaut�s autochtones. En 1995, le “National Museum of the American Indian” fit l'envoi vers la R�serve des Navajos d'un nombre de couvertures du XIXe si�cle de ce peuple, afin de d�velopper une exposition avec la participation de la communaut� locale et de permettre aux membres de la communaut�, en particulier, aux tisserands, d'avoir acc�s et d'�tudier ces tissus. Pendant le cours de cette visite, les horaires durent changer continuellement, soit � cause de circonstances impr�vues, ou m�me parfois d'assomptions erron�es. En fin de compte, le projet a r�ussi � atteindre l'�quilibre entre l'acc�s accru et la pr�servation des couvertures. La cl� de ce succ�s reposait sur la souplesse d�montr�ee par le personnel du mus�e afin de r�soudre les probl�mes tels qu'ils se pr�sentaient. TITULO—Tejido por las abuelas: veinticuatro mantas viajan a la Naci—n Navajo. RESUMEN—A medida que se espera que haya una mayor colaboraci–n entre los museos en cuyas colecciones hay material cultural ind'gena, y los pueblos nativos, es imperativo que estas colecciones sean mas accesibles a las comunidades ind'genas. El Museo Nacional del Indio Americano env'o una muestra de mantas del Siglo XIX a la Reservaci—n Navajo en 1995 para desarrollar una exhibici—n en la cual se involucr—a la comunidad y se le facilit—el acceso, especialmente a los tejedores para que pudieran estudiar las mantas. Durante el evento, los planes que se hab'a hecho tuvieron que ser modificados continuamente debido a circunstancias que no se hab'an previsto, y a veces porque se hab'an hecho suposiciones erradas. Al final, el �xito del proyecto dependi—de la flexibilidad del personal del museo para resolver los problemas a media que se fueron presentando, siempre manteniendo un equilibrio entre el acceso a las mantas y la preservaci—n de las mismas. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution, like other museums in North America, is seeking consultation, collaboration, and partnership with Native American communities in its research, exhibitions interpretation, and collections care (NMAI 1992). Through the Navajo textile project, we sought to meet this goal by traveling a selection of textiles to the Navajo reservation in 1995. The project culminated in the exhibition and publication Woven by the Grandmothers: Nineteenth-Century Navajo Textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian(Bonar 1996). Although NMAI actively lends objects to tribal museums, cultural centers, and occasionally to Native communities for ceremonial use, this project marked the first time the museum took collections objects back to the Native community that created them to develop an exhibition. As an outreach program, our priorities included providing the Navajo community access to this collection through a public display and a hands-on workshop. The workshop, in particular, was an opportunity for Navajo weavers to closely examine these early blankets. This type of increased use of collections can challenge traditionally accepted museum standards that guide collections care. NMAI is continually balancing the need to preserve and safeguard its collection while providing access and educational opportunities to the public, especially the Native community. Over the past two decades museum professionals, including conservators, have begun to integrate sensitivity issues related to indigenous cultural materials with standard museum practice. The proceedings of Symposium '86: The Care and Preservation of Ethnological Materials (Barclay et al. 1986), contain several papers in the “Conservation in the Cultural Context” section that describe museum collaborations with indigenous peoples from the Americas. Subsequent thematic conservation conferences and symposia have raised the awareness of museum professionals working with these types of collections.1Moses (1995) explained the importance of recognizing traditional Native views concerning object preservation, which may be quite different from traditional European views. For instance, some Native views do not support the indefinite preservation of all material culture but allow for its natural deterioration. Native opinions about the preservation (or nonpreservation) of material vary from culture to culture. Opposing views are sometimes found among members of the same tribe and may change over time (as within scholarship).2Clavir (1996) discussed the challenges that museum professionals, specifically conservators, face when indigenous cultural material in a museum is viewed by Native people as part of a living culture rather than part of a historic past. In these cases, preservation of the object may go beyond physical preservation and encompass cultural and even spiritual realms of preservation. The NMAI's collection of 19th-century Navajo textiles has special historical significance to the Navajo community. Woven in the mid- to late 19th century, many of these textiles were made as clothing for everyday and special use, while others were made as utility blankets that served a variety of purposes (fig. 1, p. 336). With the restriction of the Navajo to reservation life after their confinement at Bosque Redondo (1864–68), the materials, design, and use of later weaving underwent a dramatic change (Kent 1985; Hedlund 1996; Wheat 1996). For instance, later blankets were not as finely woven and were made primarily for trade to non-Indians. Prereservation blankets in good condition, such as in the NMAI's collection, had largely been removed from the reservation by the end of the 19th century by traders and dealers to be sold into the Indian art market. While collecting did help preserve these old blankets, it has also made them inaccessible to many Navajo people. Now many of these textiles are in collections outside of the Navajo Nation and are frequently regarded as two-dimensional art objects.

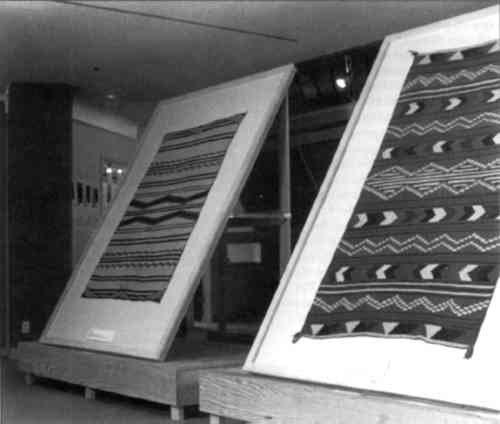

2 PROJECT HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENTThe Navajo textile project grew from a documentation survey of approximately 400 19th-century Navajo textiles, started in 1986 by assistant curator Eulalie Bonar, in the collection of the Museum of the American Indian-Heye Foundation (MAI–HF). The idea of taking these textiles back to the reservation was rooted in an early conversation among Bonar, Harry Walters, director of the Hatathli Museum at Navajo Community College (NCC, now Din� College), and D. Y. Begay, a Navajo weaver and project consultant, then a visiting artist at the museum. The MAI–HF collections were transferred to the Smithsonian's new NMAI in 1989, and in early 1995 museum staff began preparations to realize a temporary return of 24 blankets to the Navajo community (Bonar et al. 1996). The Ned A. Hatathli Museum on NCC's campus in Tsaile, Arizona, was chosen as the site to host the event. Tsaile is located on the Navajo reservation about 72 miles north of Window Rock, Arizona, the Navajo Nation's capital. Except for the college campus and a small convenience store, the nearest businesses and restaurants are in Chinle, about 30 miles to the west. Though the location initially seemed remote, it is important to recognize that Tsaile is located at the center of the Navajo world and proved to be a good choice for Navajo access to the exhibition and workshop. Walters, whose background includes a degree in cultural anthropology and museum training with the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, became the main contact on the reservation. Several months prior to the event, NMAI staff traveled to the Hatathli Museum to review the facilities and work out logistical details for shipping, staff housing, and publicity. Walters worked with visiting staff to complete NMAI's standard loan agreement for the NCC facility, noting light levels, pest control procedures, and climate control. The museum, located within a multipurpose building, was extremely secure, with the local Navajo police department located on the first floor. As anticipated, there were challenges. The Hatathli Museum fell short of NMAI's loan standards in several areas. Completed in 1976, the facility was designed to include a state-of-the-art museum, but at the time of the loan its climate control system was not working and the loading dock access was only serviced by a small passenger elevator. However, with the full support of the Hatathli Museum staff to solve access difficulties and NMAI staff on site to monitor the loan, the conditions were considered adequate. The problems with the facility were deemed minor compared to the importance of bringing these textiles back to the Navajo community. The loan lasted approximately 2 weeks. We scheduled 3 days for installation and 3 days for a display open to the public. The following 2 days were designated for the workshop: the first day was open to all interested weavers, and the second day was reserved for a small group of invited weavers. The final few days were left for deinstallation. Input from Navajo people was incorporated at all levels of the project, including planning and implementation. We were fortunate to have several Navajo staff within NMAI assisting with the project. Four of the eight staff who traveled to Tsaile were enrolled members of the Navajo Nation. In addition, a group of eight advisers, both Navajo and non-Native scholars and weavers outside the museum, guided the project. 3 CONSERVATION CONCERNSThe conservator's role in the project was to reduce the risk of damage to the blankets while they were in Tsaile. This responsibility included assessing the condition of the blankets prior to travel, working with NMAI's Exhibitions Department to develop mounts, installing the textiles on site, and acting as a “handler” during the workshop. Hands-on access to the textiles was integral to the workshop; participants would be allowed to closely examine weaving details. The importance of handling and examining these textiles by Navajo weavers is similar to that of curators and scholars examining art objects in other museum collections. A notable difference is the close spiritual connection many Native people feel toward their cultural material. While the Conservation Department fully supported the museum's outreach goals, the conservator was apprehensive about placing collection objects at risk during these events. The reality of working in a museum like NMAI means the conservator's priority is to protect objects such as these textiles for Native people, not from them; preservation and access must go hand-in-hand. Both NMAI and Hatathli Museum staff were sensitive to these issues. Everyone involved worked together to minimize the risk of damage without hampering the objectives of the project. 3.1 CONDITION OF THE TEXTILESOf the original blankets selected for travel, several had to be excluded because of structural weakness from wear and in some cases severe insect damage. In these cases more stable substitutes were chosen. Fortunately, many of the textiles had been recently treated and stabilized by outside contract conservators. One textile (9.1910), a woman's manta or shoulder blanket dated to about 1860, exhibited areas of weakness on two edges including weft loss exposing the warps and abraded selvage cords. The damage appeared to be from wear, not insect damage. While these areas had been stabilized, they were still vulnerable to damage if handled. However, both Bonar and Begay felt this piece would be especially significant to contemporary weavers because it was a typical blanket that showed signs of wear. It was interesting because of its overall twill tapestry structure and simple design. Damaged areas also revealed structural details. For instance, one side of the blanket had blue warps, the other side white; lacing details at the warp turns were also visible. After some consideration, this piece was allowed to travel on the condition that it be carefully monitored during the loan. Some of the textiles had minor insect damage from previous infestations. In some natural history and ethnographic collections, past use of residual pesticides such as arsenic and mercury compounds presents a hazardous handling situation. Most often these pesticides were used on taxidermy specimens or furs, but sometimes on textile materials as well (Hawks and Williams 1986). There is no recorded history of any such residual pesticides being used on textiles in the collection. The Conservation Department continually tests suspicious residues when found. To date, all test results have been negative. Therefore, we felt handling of these textiles did not pose a danger to staff or participating weavers. 3.2 MOUNTING STRATEGYUnlike most museum exhibitions where mounts are used solely for display, this project required mounts for both exhibition presentation and workshop support (but not for travel). Conservation requirements included the following: the textiles had to be displayed flat and fully supported and the mounts had to minimize handling during the installation and the workshop. The NMAI exhibitions staff designed elegant, lightweight slant boards that were fabricated quickly and inexpensively in three standard sizes (fig. 2). Because the blankets were mounted for only nine days, conservation standards for materials were relaxed to some extent. For example, wood products were not coated, and Gatorfoam was used instead of a more archival material.

The Gatorfoam boards were covered with an undyed cotton fabric attached with poly (vinyl acetate) adhesive. Poplar wood trim was used to frame the covered boards. A hinged plywood gateleg attached along the upper back edge allowed the entire mount to fold flat easily. An aluminum side brace attached to the frame locked the gateleg into place with the board at a 70� angle. The lightweight, folding-leg design enabled the mounts to support textiles during the workshop as well as in the exhibition. The mounts greatly minimized handling by acting as support boards in transporting the textiles from the gallery to the adjacent workshop room and by serving as horizontal examination surfaces when placed on tables (fig. 3). Blankets did not need to be removed from their mounts until they were rolled for crating at the end of the event.

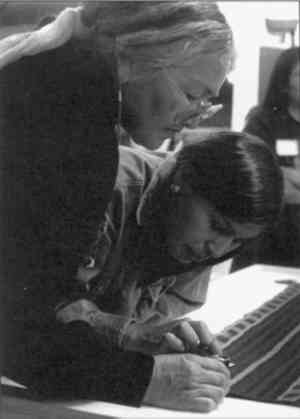

It was disheartening to discover upon our arrival in Tsaile that about one-third of the mounts were damaged in shipping. The Gatorfoam was dented and in one case punctured, probably by a forklift. Additionally, some of the wood trim was separated or broken. We managed to salvage all but one mount, forcing us to eliminate only one textile from the display. We were, however, still able to make this blanket available during the workshop. Textiles were fastened to the slant boards by pinning along the upper edge and sides with stainless steel insect pins. This strategy was chosen so that all areas of the front and back would be visible for examination; other systems such as Velcro or pinning bands stitched to the back would have covered part of the textile. After pinning the blankets to the slant boards, the mounts were placed on 1-ft.-high plywood platforms fabricated by the NCC woodshop. The platforms elevated the slant boards from the gallery floor, placing the textiles at eye level and creating a toe-edge that distanced the viewer slightly. No other physical barriers were used. During the installation NMAI staff worked with Hatathli Museum staff and trained high school volunteers in handling and mounting techniques. The extra help provided by the students was invaluable in setting up the gallery. Not only did they supplement our initial two-person installation team before the balance of the NMAI staff arrived, but they also were provided a unique opportunity to learn about museum work through firsthand experience. 3.3 TOUCHING AND SIGNAGE ISSUESShortly after the display opened to the public, it became clear that touching and signage issues needed to be reevaluated. It was the conservator's understanding that the public display was to be completely “hands-off,” while the workshop event was to be controlled and supervised “hands-on.” For the public display, some staff from both NMAI and the Hatathli Museum assumed that we would post “Please Do Not Touch” signs. Others felt that any physical barriers or signs would be intrusive to Navajo viewers. In traditional museum settings, some Native viewers feel distanced and alienated from their cultural heritage by such barriers. NMAI staff did not want to offend Navajo visitors, especially on the Navajo reservation, where we were guests. It was also assumed by some Navajo staff and advisers that “Please Do Not Touch” signs would be unnecessary because Navajo visitors simply would not touch out of respect. Initially NMAI staff and student volunteers were stationed around the gallery to ask people politely not to touch the textiles. It became immediately clear that many visitors did feel inclined to touch, and the verbal directions could be interpreted as insulting. One impassioned response was, “Why don't you have 'Do Not Touch' signs if you don't want us to touch!?” There was clearly a confusing double standard regarding the touching policy; workshop participants could touch, but other visitors could not. In discussions about the issue, one Hatathli Museum staff member suggested large “Do Not Touch” signs printed in red letters. To remedy the situation without drastic or intrusive measures, the following compromise was reached: four 8 � 10 in. signs that read, “Please Ask a Staff Member If You Want to Touch a Blanket,” were posted in several locations around the gallery. Additionally, small “Please Do Not Touch” signs were placed on each platform beneath the object labels. This placement allowed the viewers to see the sign as they approached the textiles and read the label copy. The 10 most stable and sturdy textiles were designated as “touchable” in the lower unpinned corners, and identified with a star on their labels. Upon request, staff led interested visitors to appropriate textiles that could be handled. In addition, greeters politely explained the handling policy (translated into Navajo when necessary) to visitors as they signed the guest book at the gallery entrance. Our new approach was well received, and the incidents of random handling became virtually nonexistent. Visitors did approach staff members asking to touch. This interaction between staff and visitors promoted discussions and questions concerning the blankets, display, and NMAI. Touching was always gentle and respectful: most visitors seemed only to want a brief physical connection with the weavings. 4 THE WORKSHOPCreating access to the textiles through the workshop was the primary purpose of bringing the blankets to Tsaile. Although many weavers may have access to Navajo weavings in New Mexico and Arizona museums, only some have the opportunity to study old blankets of this type closely. Additionally, the workshop environment encouraged group discussion and interaction, presenting an opportunity for exchange of knowledge between NMAI staff and weavers (fig. 4, p. 341). It was planned that information gathered would become primary source material for the exhibition Woven by the Grandmothers.

The workshop was originally scheduled for two days following the close of the display. However, local press coverage of the display was late, causing community interest to gain momentum just as the show was about to close. In order to allow more visitors to see the blankets, we decided to extend the display to run concurrently with both workshop days. This decision complicated the logistics of the workshop—How could we now keep the second day exclusive to invited weavers?—and reintroduced the handling issue. When some invited weavers arrived two days early, and others filtered in often accompanied by various generations of their families, we quickly dropped any plans for restricting the access or abiding by our carefully choreographed schedules. We were working in the Navajo community where flexibility, diplomacy, and reciprocity were essential as we adjusted to Navajo ways. In fact, we were already regretting that we did not plan for a longer visit. Approximately 80 people participated in the two days of the workshop. All participants were asked for permission to be included in the museum's documentation, consisting of photography, video, and audio recording, as well as conventional note taking by staff. Those who did not want to be recorded in any way were identified by a color-coded name tag to visually inform staff of their decision. Each workshop day began early with a Navajo blessing for the blankets and participants, followed by a welcome and introduction by Walters. Interpretation in both English and Navajo was given throughout the event by museum staff, advisers to the project, and volunteers, some of whom also assisted as handlers. NMAI's conservator presented a standard museum-handling orientation and explained how to use head loupes, probes, and linen testers. Weavers were given the option of using white cotton gloves or making sure their hands were clean before handling. About one-quarter of the weavers chose to wear the gloves. Many weavers dressed in their finest, with beautiful turquoise and silver jewelry, to attend this special event. We felt it was inappropriate to ask participants to remove their jewelry before handling the textiles. Weavers selected blankets they wanted to examine. The gateleg of a slant board was then collapsed, and the mounted textile was carried into the adjacent workshop room. The textile mount assemblage was placed flat on a table for examination. The workshop room was large enough to accommodate the study of two textiles at a time. Additionally, analysis sheets with information on yarn and fabric structure, dye analyses, and estimated dates of fabrication were posted in the room, and copies were given to interested parties. These analysis sheets, based on research by the late Southwest textile specialist, Joe Ben Wheat, were the focus of discussion and debate (Bonar et al. 1996, 181–95). Some weavers disagreed with attributed mid-19th-century dates because the textiles were in such good condition. Others found results of the dye analysis hard to believe, since red yarns identified as cochineal were very bright in color, appearing more like synthetic-dyed yarn. During the workshop, no textile ever left the support of its mount, though corners and sides were turned over and weaving details scrutinized. A few detached yarn fragments were found on the slant boards during the final packing. Most of these yarns were from augmented corner tassels. Several small fragments were from weak selvage cords. Detached fragments were saved and later placed in the textile's conservation file. The losses were fewer than anticipated and seemed minuscule compared with the emotional response of the participants. 5 CONCLUSIONSThe project was a success on many levels. NMAI staff (both Navajo and non-Navajo) were educated in the challenges of working within a reservation community. As museum professionals, we learned to be resourceful, flexible, and careful about making assumptions when working with Native communities. While having Navajo staff and consultants participate in the project at all levels contributed to its success, we were still unable to account for all of the subtleties of working in the Navajo community, especially in regard to the workshop. Cultural differences concerning time, for instance, affected our schedules. In the Navajo community, as in many Native communities, devotion to schedules is superseded by family obligations and proper etiquette. For example, on the second day of the workshop, introductions among the weavers, scheduled for one hour, lasted for more than three. We also miscalculated the time required for bilingual translation. Complete interpretation was impossible; some important information was not lost in translation, but without translation. Our plans were also disrupted by other unexpected events and complications such as lack of advance publicity and shipping damage to the mounts. Limited access to stores and supplies also impeded our ability to make onsite changes and repairs. We had planned the first workshop day for all interested weavers and the second day for a small group of invited weavers that would allow for a more intimate and focused discussion. In retrospect, it should have been clear that this arrangement would be impossible to maintain. Because the Navajo Nation is the largest Native American reservation, extending into Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah and covering more than 27,000 square miles, weavers had to travel varying distances to visit Tsaile. This was a destination trip, not an incidental one. Not all of the weavers were able to drive, and most (if not all) brought family members along. We could not bar families from the workshop room; nor could we turn away weavers who had arrived the day before the designated workshop days. Ultimately, the unanticipated breadth of participation became one of the workshop's greatest strengths. The exchange of information and cultural knowledge among participants was intergenerational and reinforced for many the sustained cultural importance of Navajo weaving. Mothers taught daughters and grandchildren, and fathers, brothers, and uncles brought children to see these magnificent expressions of their heritage. During the display and workshop more than 800 people, nearly all Navajo, visited our display at the Hatathli Museum, from many reaches of the reservation and beyond. For the Navajo people, the process of weaving is intertwined with their culture, history, and family relationships and is a source of great pride. Few weavers from the reservation ever have the opportunity to view the blankets in NMAI's collection without making a daunting journey to the East Coast. Even fewer would ever get the chance to study them closely and share their observations and ideas with one another in a community environment. Many museums, especially large institutions like the Smithsonian, are often considered by Native people to be inaccessible repositories of their cultural treasures. Outreach programs such as this one are fundamental to the mission of the National Museum of the American Indian in perpetuating and supporting Native culture within Native communities. This is where the balance between collection protection and collection use is evolving and must continue to evolve. The exchange among the weavers, community members, and museum staff during our visit to Tsaile was rewarding for all involved. We learned more about the personal significance of the blankets to the Navajo community and gathered information for the exhibition and publication. Most important, the community appreciated having the blankets returned to their homeland, if only for a brief visit. 6 AFTERWORDIncorporating information and commentary gained from this event, Bonar developed the exhibition and publication, Woven by the Grandmothers: Nineteenth-Century Navajo Textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian, with three co-curators: D. Y. Begay, Wesley Thomas, and Kalley Musial Keams, all of whom are Navajo weavers. In the final exhibition design, the majority of the blankets were displayed on humanlike forms to show how they may have been worn. The exhibition opened in October 1996 at NMAI's George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. Later venues included the Navajo Nation Museum, Library, and Visitors Center, Window Rock, Arizona; the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.; and the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. Woven by the Grandmothers served as the inaugural exhibition for the opening of the new Navajo Nation Museum, Library, and Visitors Center in 1997. The exhibition was enthusiastically received by the Navajo community (Shebala 1997); the museum was booked every day with visiting groups from all over the reservation. An excerpt from a local newspaper article illustrates its impact: “These creations of the Navajo ancestors were displayed the way they were intended–as clothing. And as you walk through the softly lit exhibit you cannot help but see how magnificently beautiful and fiercely proud our people, the Navajo, looked” (Sunny Side 1997). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSFor their contributions and support, we thank Bruce Bernstein, Eulalie Bonar, Andrea Hanley, George Horse Capture, Marian Kaminitz, Emily Kaplan, Leslie Williamson, Cheryl Wilson, and Mary Jane Lenz. We thank all of the people who made this project a success, especially the Navajo weavers who participated in the workshop. NMAI Navajo staff involved with this project were Andrea Hanely, project manager; Kathleen Ash-Milby, assistant curator; Kenn Yazzie, collections handler; and Keevin Lewis, public outreach coordinator. Outside advisers to the project were Clarenda Begay, D. Y. Begay, Ann Lane Hedlund, Kalley Musial Keams, Bob and Ruth Roessel, Wesley Thomas, and Harry Walters. Hatathli Museum staff and volunteers were Edsel Brown (Din� College), Darren Wagoner, Bobby Yoe, and Winnifred Tsosie. Kathy Tabaha from the Hubbell Trading Post, National Park Service, was an additional volunteer handler for the workshop. We also wish to thank Jeanne Brako and Robert Mann of Art Conservation Services in Denver who treated many of the blankets. NOTES1. These conferences and symposia include “The Conservation of Sacred Objects,” general session papers, American Institute for Conservation 19th Annual Meeting, Albuquerque, 1991; “First Peoples Art and Artifacts: Heritage and Conservation Issues,” professional papers presented at the Art Conservation Training Programs 18th Annual Conference, Kingston Ontario, 1992; “Native American Collections: Preserving Objects Versus Preserving Culture,” colloquium presented at Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1994; “Caring for American Indian Cultural Materials: Policies and Practices,” symposium sponsored by Fashion Institute of Technology and the National Museum of the American Indian, New York, 1996; and “Critical Issues in the Conservation of Ethnographic Materials,” workshop presented at Canadian Association for Conservation of Cultural Property 24th Annual Conference, Whitehorse, Yukon, 1998. 2. We have found it best to consult with individual tribes and develop a continuing relationship, whenever possible. REFERENCESBarclay, R., M.Gilberg, J. C.McCawley, and T.Stone, eds.1986. Symposium '86: The care and preservation of ethnological materials. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Conservation Institute. Bonar, E. H., D. Y.Begay, and K. E.Ash-Milby. 1996. Woven by the Grandmothers: Nineteenth-Century Navajo Textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian: Three perspectives on a museum project. Native Peoples Magazine9(4):36–42. Bonar, E. H., ed.1996. Woven by the Grandmothers: Nineteenth-century Navajo textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. Clavir, M.1996. Reflections on changes in museums and the conservation of collections from indigenous peoples. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation35:99–107. Hawks, C. A., and S. L.Williams. 1986. Arsenic in natural history collections. Leather Conservation News2(Spring):1–4. Hedlund, A. L.1996. “More of survival than an art”: Comparing late nineteenth- and late twentieth-century lifeways and weaving. In Woven by the grandmothers: Nineteenth-century Navajo textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian, ed.E. H.Bonar. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 47–67. Kent, K. P.1985. Navajo weaving: Three centuries of change. Santa Fe: School of American Research. Moses, J.1995. The conservator's approach to sacred art. Western Association for Art Conservators Newsletter17(3):18. NMAI. 1992. National Museum of the American Indian collections policy. Washington, D.C.: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. Sunny Side. Supplement1997. Ancestors. Sunny Side: Navajo Times 5(August):12–13. Shebala, M.1997. Emotional reactions to Navajo rug exhibit. Navajo Times, August 14. Wheat, J. B.1996. Navajo blankets. In Woven by the grandmothers: Nineteenth-century Navajo textiles from the National Museum of the American Indian, ed.E. H.Bonar. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 69–85. AUTHOR INFORMATIONSUSAN HEALD received a B.A. in chemistry and anthropology from George Washington University in 1985, and an M.S. in art conservation with a major in textiles and minor in objects from the University of Delaware/Winterthur Art Conservation Program in 1990. Following graduate school she was a postgraduate fellow at the Smithsonian Institution's Conservation Analytical Laboratory and the Cooper-Hewitt Museum. She served as textile conservator for the Minnesota Historical Society before joining the Conservation Department at the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, as textile conservator in 1994. Address: NMAI Cultural Research Center, 4220 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746; Heald@ic.si.edu KATHLEEN E. ASH-MILBY, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation and assistant curator at the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, received a B.A. in art history from the University of Washington in 1991 and an M.A. in art history with a specialization in Native American art history from the University of New Mexico in 1994. In 1993 she joined the NMAI Curatorial Department as a research assistant and also served as acting collections manager. Her work with the Woven by the Grandmothers project included formatting and condensing Wheat's analysis sheets for the publication's artifact list. Her research specialty is 20th-century and contemporary nontraditional Native American art. Address as for Heald; Kathleen@ic.si.edu This article was originally presented as “Woven by the grandmothers: 24 blankets go back to visit the Navajo reservation,” General Session: Collaboration in the Visual Arts, at the American Institute for Conservation 24th Annual Meeting, Norfolk, Virginia, June 10–16, 1996.

Section Index Section Index |