THE METHODS AND MATERIALS OF MARTIN JOHNSON HEADE

ELIZABETH LETO FULTON

7 PAINTING TECHNIQUES

In the 1840s, in the beginning of his career, Heade painted mostly with a paste vehicular paint in a simple structure. The paint layer from this period is generally smooth with slight impasto in the more thickly painted areas. By the late 1850s and into the 1860s, as Heade became more accomplished, he experimented more with impasto, even becoming almost Impressionistic, as in April Showers(fig. 11). During this period Heade added to his repertoire a vocabulary of technical language not seen in his paintings prior to 1858. His paint structure became multilayered as his style became more sophisticated. In addition, Heade experimented with many unique brush strokes and techniques that would become the hallmarks of his style in the 1860s.

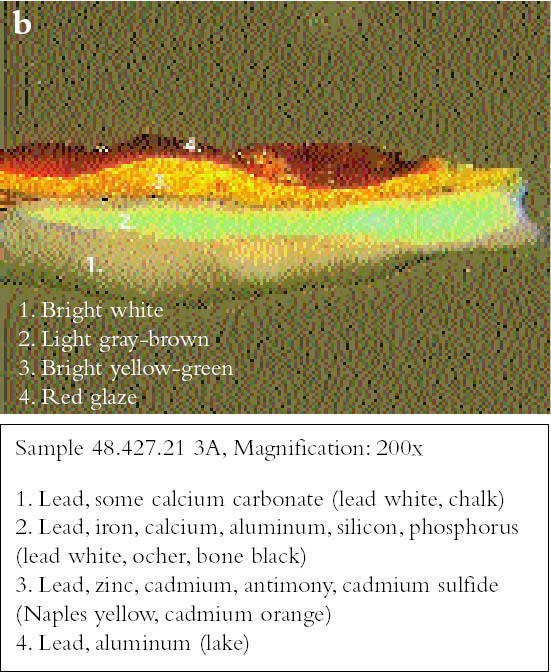

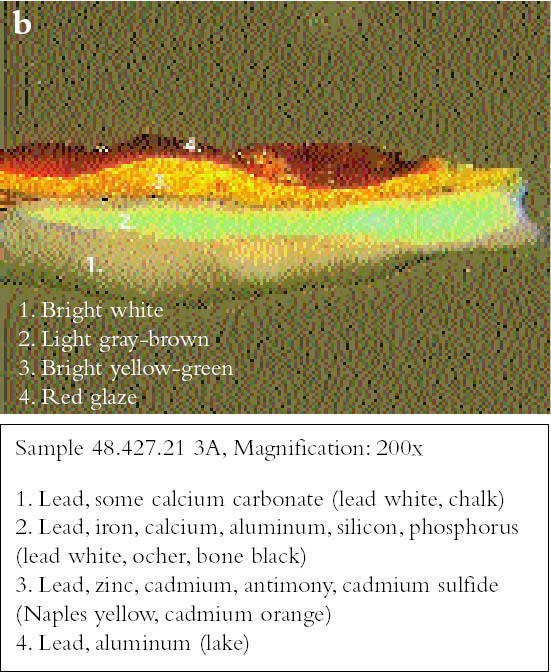

One of the most characteristic techniques Heade developed was glazing over bright, reflective impasto to imbue his subjects with light. This technique is well illustrated in Sunset on Long Beach (ca. 1867, S176) (fig. 12). In using this device to paint areas that served the purpose of emanating light, Heade applied a thick underlayer of bright, reflective white paint impasto. On top of this thick white underlayer, he generally applied thin, transparent glazes of red, orange, and yellow (for the clouds, sunsets, sunrises, and throats of orchids); transparent reds, purples, greens, and blues can also be seen in some of the hummingbirds. These Luminist effects work well because the bright white underlayer reflects light through the glazes, much like light passing through stained glass, emitting a luminosity and intensity of color not achievable by opaque paints mixed with white on the palette. This technique was first noted in 1858 in The Swing—Children in the Woods and became further refined, reaching its pinnacle in his sunsets, orchids, and hummingbirds (Wright 1999). The year 1858 was also when Heade was exposed to the Pre-Raphaelites, who were known to work with these “stained-glass” effects (Sheldon 1998) and appears to be the seminal year for this technique that Heade transforms into a device all his own, giving intensity to the clouds, sunsets and sunrises, orchids, and hummingbirds.

Heade used other characteristic technical devices to emphasize certain qualities in his paintings. To emulate the feeling of a lowland estuary in his land-scapes, which were extremely horizontal in format, Heade used long, adjacent horizontal brush strokes of complementary colors (usually dull reds and greens) to add interest to otherwise monotonous areas (fig. 13). He contrasted the horizontal, flat middleground with detailed vegetation in the form of stippled or spiked plants, sometimes punctuated with flecks of bright colors, a technique most likely borrowed from Church (fig. 14) (Wright 1999, 175). Heade added these bright flecks to dark or neutral areas, often using complementary colors. This technique is later fully expressed in his hummingbirds and orchids that are also surrounded in the background by muted complements to further intensify the brilliant colors of the subjects.

In addition, as April Showers illustrates, a stippling effect fully developed in Heade's blossoming trees, which very often flank the smooth middleground (see fig. 11). Other techniques found in Heade's land-scapes include comma-like brush strokes, subtractive strokes (using something stiff like the brush ferrule to remove paint from the center of the stroke), and distinctive, calligraphic, hooked branches, commonly found in his hummingbird pictures.

In many landscapes glazing is often found in the shadows surrounding the base of trees, rocks, or other compositional elements. Scumbling, which plays a lesser role, is found in Heade paintings, usually in the skies and mountains in the backgrounds of early paintings. However, more often than not, the skies are painted with glazes applied in imperceptible brush strokes in smooth, liquid areas of limpid colors, giving a sense of infinity to the space and air they depict.

Fig. 11.

Martin Johnson Heade, April Showers, 1868, oil on canvas, 19 7/8 x 40 1/4 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865, 47.1173, detail showing Impressionistic brushwork and stippling effect

|

Fig. 12.

Martin Johnson Heade, Sunset on Long Beach, 1867, oil on canvas, 10 1/8 � 22 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865, 47.1159; b, detail of sun showing glazing over bright, reflective impasto

|

Fig. 13.

Martin Johnson Heade, Newburyport Marshes, ca. 1866–76, oil on canvas, 13 1/4 x 26 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of Maxim Karolik, 64.441, detail showing horizontal brush strokes of complementary colors

|

Fig. 14.

Martin Johnson Heade, South American River, 1868, oil on canvas, 26 x 22 5/8 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865, 47.1153, detail of flowers in fore-ground demonstrating Frederic E. Church's influence

|

Fig. 15.

Martin Johnson Heade, The Swing—Children in the Woods, 1858, oil on canvas, 11 1/2 x 15 1/4 in., private collection, New York, courtesy of Kennedy Galleries, detail showing Heade's first use of transparent pigments found in the study

|

Fig. 16.

Martin Johnson Heade, Vase of Mixed Flowers, ca. 1872, oil on canvas, 17 1/4 x 13 1/2 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865, 48.427; b, cross section (200x) showing glazing technique

|

|