SHORT COMMUNICATION ORIGINAL PATENTS AS AN AID TO THE STUDY OF THE HISTORY AND COMPOSITION OF SEMISYNTHETIC PLASTICSSILVIA GARC�A FERN�NDEZ-VILLA, & MARGARITA SAN ANDR�S MOYA

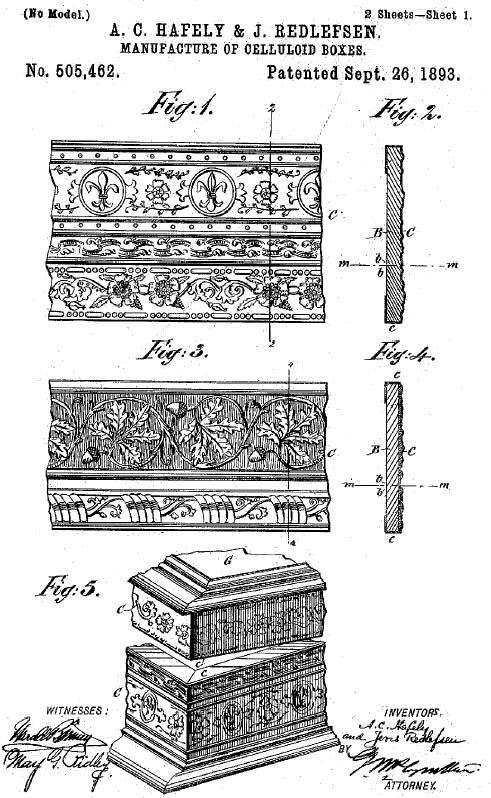

1 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING OLD PATENTSA patent registers the right of ownership of an invention or technological improvement, protecting the inventor and guaranteeing his or her exclusive right in respect to its manufacture, use, and sale. A patent is frequently claimed not by the inventor but by a company or a representative. Such rights in an invention can also be bought or sold, in which case it will not be the inventor who undertakes industrial production of the product or material concerned. To apply for a patent, the following details must be given: state of the art, nature of the technical problems that this invention solves, and detailed description of the invention and how it works, accompanied by illustrations if necessary. The first patents for semisynthetic materials were registered in the United States and Great Britain in the 19th century, by the actual inventors. Synthetic materials, on the other hand, belong to the age of plastics, in which research is undertaken by large companies (e.g., ICI and Du Pont) that then claim and register patent rights. The rights conferred by registration of a patent are always restricted territorially, and so when the first semisynthetic molding plastics were developed, a patent for a given plastic registered in the United States conferred no rights whatsoever concerning production of the same material in Great Britain. This situation prompted a race to patent any new plastic material in all countries. The date of the patent for a material or artifact indicates the date when it was registered; this is not generally the date of first industrial production, which would normally take place some years later. However, there are exceptional cases of objects manufactured prior to the patent date. For instance, polymers were developed and used for military purposes years before they were patented and commercialized. Indeed, patents relating to materials and artifacts developed for military purposes have had their publication delayed or have not been published at all, as happened particularly in the years between the two world wars (Van Dulken 1999). Another exception is vulcanized rubber, which was manufactured by Goodyear before the date of the patent. As the industrial importance of such substances increased over time, however, inventors became aware of the need to patent them before commencing production. Despite these exceptions, the patent date helps to place the object chronologically. Generally, it provides the date before which the material concerned could not have been manufactured (Wohler 1998). Many materials and objects made with semisyn-thetic plastics were never patented, for a variety of reasons, including failures in the application process, ignorance of the patent system, or lack of financial resources. Between 1852 and 1883, a British patent cost �25 and the renewal fees could be as high as �150, a major financial outlay at that time (Van Dulken 1999). Many 19th-and 20th-century objects bear an inscription containing the date of the patent, which allows for a preliminary approximation of the date of the object. However, given the possibility of error in the inscription, it is always advisable to check the date by examining the original patent and checking its content. If the inscription had a number only, the data can be determined by checking relevant patent year–number tables supplied by patent offices in every country. The number of a patent and the probable date of its invention or manufacture may also furnish a key to the nationality of the patent, since numbering varies from country to country depending on the dates. A patent number in the region of 100,001 dated c. 1870 would be from the United States, for example, but if c. 1916, from Great Britain; if c. 1873, from France; and if c. 1898, from Germany. A study of old patents can be complicated by the difficulty of locating them; one of the chief problems is that they have not always been numbered according to a single system. British patents registered between 1617 and 1852 originally lacked numbering and were not published. Objects from this period therefore do not bear patent numbers, although they may bear inscriptions containing the word “patent” followed by the name of the inventor or applicant. With the modernization of patent law in 1852, the 14,359 patents granted up to that time were numbered consecutively in the format no./year (e.g., no. 1/1617; no. 425/1720). This format was maintained up to number 14,359 (no. 14.359/1852), and those patents were published during the 1850s. In 1852 a new system was introduced in which numbers started back at one every year. At this time patents also began to include certain specifications regarding the description of the invention. New changes were introduced in 1916, when continuous numbering began. This commenced with the number 100,001 The first U.S. patent was issued on July 31, 1790, to Samuel Hopkins of Philadelphia. Between 1790 and 1836, patents were not numbered, but they did show ownership and date. The first numbered patent was granted on July 13, 1836; from then on, the numbering has been continuous and consecutive. Since 1790, the United States has issued more than 6.5 million patents. 1.1 METHODOLOGY OF SEARCH FOR OLD PATENTSResearch into old patents can be fairly complicated, although recent advances make it possible to find old patents through the Internet. To locate a patent and purchase copies, it is essential to know the patent number and the year of the document. Since October 1998, a network called esp@cenet (website at ep.espacenet.com/ [accessed July 27, 2005]) has furnished information from the patent offices of some countries; the coverage of this search is different in each country. Esp@cenet lists patents from the European Patent Office (EPO), World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO), Japan, and many other countries. Unfortunately, only a very few pre-1920 British patents are available via the Internet. Another way of searching for British patents is through the British Library, which requires precise details about the subject of the research. This library holds patent records dating back to 1617. If the search is more complex, a research service is available to researchers (">research@bl.uk [accessed July 27, 2005]). If the patent number and year are known, photocopies of the patent specifications can be procured through the British Library Document Supply Centre (dsc-customer-services@bl.uk [accessed July 27, 2005]) or the Leeds Patent Information Unit (piu@leeds.gov.uk [accessed July 27, 2005). U.S. patents are available over the Internet through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) (website at www.uspto.gov/ [accessed July 27, 2005]), whose database allows access to patents granted from 1790 to the present. Patents from 1790 through 1975 are searchable only by patent number and current U.S. classification and only images of these patents are available. For unnumbered U.S. patents (1790–1836) a search can be run by patent number if an X is put in the number field. Many of these old patents are not yet accessible online. All patents from 1976 onward are available in full text, and there are numerous different search criteria—title, issue date, application date, inventor name, etc. 1.2 LIMITATIONS OF PATENT RESEARCHPatent research can furnish very useful data on a given item; nonetheless, the information patents contain must be checked against other documentary sources such as maker's archives, registry dossiers, and product catalogs. In some cases patents contain erroneous or ambiguous data, which may even have been inserted intentionally to confound competitors. A number of factors can hinder accurate identification and dating of an object from its patent mark. First, the mark may not contain enough information to allow proper interpretation. Second, the patent it refers to may have never been published. Moreover, the patent mark may take many forms. For example, no rules have ever been established for British patent marks. There might be the name of the inventor or the company followed by the patent number, or the letters BP (British Patent) or PAT (Patent) followed by the patent number. The date shown may be the date the patent was granted or the date the patent application was submitted. Some inscriptions read only “patent pending,” “patent applied for,” or “patented.” For these, a search is possible only if the name of the maker is known and if the maker was also the applicant (in many cases it was not). Sometimes an object may bear a patent number corresponding to an application that was never granted. There may also be confusion among patent numbers, registered designs, and production numbers. In other words, a number on an object is not necessarily a patent number. Futhermore, some references to patents may be false, put there to discourage competitors. 1.3 PRACTICAL EXAMPLES OF PATENT RESEARCHResearch into the patent for an object not only provides data on the date of the patent, but it can also furnish information on the inventor and sometimes on the material with which the object was manufactured.

In other cases, however, the patent makes no reference to the material with which the object was made, as in the example of a banjo tailpiece bearing the inscription “Sept. 21 F&C PAT 1886”(fig. 2). The initials F&C refer to the American company Fairbanks & Cole (1880–90), which engaged in the manufacture of banjos and various banjo parts. As already indicated, searches for American patents from 1790 to 1975 can only be done online through the USPTO using two search criteria: patent year–number and current U.S. classification. It is easier to search using the patent number. Using the information on this tailpiece, the first step is to look for the patent numbers corresponding to 1886 by looking at patent–year number table. This search shows that the first patent of that year was numbered 333,494 and the last was 355,290. The next step is to look for the numbers of patents registered on September 21, 1886. The range of numbers registered on this date is 349,294 to 349,677. Finally, a search within this range (this is the most laborious part of the research) turns up patent 349,308, applied for by Frederick H. Hodges and entitled “Banjo Tail-Piece.” This patent provides a detailed description of the design and the manufacture of this piece but makes no reference to the material from which it is made.

|